The dark side of Toy Story

AF archive / Alamy Stock Photo

AF archive / Alamy Stock PhotoAs Pixar’s classic animation turns 20, Nicholas Barber finds out what made the tale of Woody and Buzz Lightyear so special.

It’s a scene from the creepiest of Philip K Dick-inspired science-fiction thrillers. Stranded in a hostile environment, a man discovers that everything he knows about the world is a lie. All of his memories are fake, all of his convictions wrong. He isn’t the hero he assumed he was. He isn’t even an individual. He is an automaton, manufactured from metal and plastic, his only purpose to amuse his creators. No wonder Buzz Lightyear gets so depressed.

It’s exactly 20 years since audiences first saw that scene in Toy Story, Pixar’s debut feature-length cartoon. Heralded as a groundbreaking triumph in 1995, the film is now enshrined as a classic, and every other Hollywood studio has copied its innovations: its eerily realistic digital animation, its snappy screwball dialogue – co-written by Buffy/Avengers mastermind, Joss Whedon.

But the film’s most radical element, and the one which hasn’t been imitated by any other studio, is its theme of disillusionment. As hilarious and heartwarming as Toy Story may be, its impressively downbeat thesis is that you’re not special, you’re the same as everyone else, and you won’t be content unless you resign yourself to your unremarkable fate. That’s quite something from a cartoon co-starring a talking Mr Potato Head.

Disney/Pixar

Disney/PixarIdentity crisis

Just in case you haven’t seen it, the premise of Toy Story is that our toys come alive when we’re not looking. But what they like best is to be played with by human beings. Buzz Lightyear (voiced by Tim Allen) is the exception. A Space Ranger action figure belonging to a boy named Andy, he believes that he really is an intergalactic superhero, but that doesn’t stop him becoming Andy’s favourite plaything, much to the annoyance of a cowboy toy, Woody (voiced by Tom Hanks).

Eventually, Woody comes to accept Buzz, and Buzz comes to accept his true identity. It’s a happy ending, sort of. But you have to wonder ... given how cheerful Buzz was when he thought he was a Space Ranger, why should we be glad about the brief life of slavery that he’s got to look forward to?

Disney/Pixar

Disney/PixarAfter all, the sequence in which he realises that he is actually a mass-produced doll is horrifying in any number of ways. First, there is the matter of where it happens. When the penny drops, Buzz isn’t in Andy’s sunny family home, but in the house next door, where the sadistic Sid is busy dismantling, melting, and otherwise mistreating every toy he can get his hands on. In the circumstances, Woody’s claim that “bein’ a toy is a lot better than bein’ a Space Ranger” can’t help but ring hollow.

Second, there is the sanity-snapping moment when Buzz catches a TV advert for his very own toy range, and sees a Kubrickian shot of shelves stacked with his doppelgangers. Third, there is his understandably extreme reaction. Having drunkenly wailed about the cruel cosmic joke of his existence, Buzz tears a sticker off his arm – a self-mutilation which will disturb anyone who has ever peeled off a plaster.

In 99 out of 100 movies, Buzz would then assert his independence. He would declare that it was up to him whether he was a toy or not, and he would race off into the sunset, bellowing his battle cry, “To infinity and beyond!” But in Toy Story, that option is never mentioned. Buzz immediately puts all thoughts of saving the galaxy behind him, and gets on with returning to his master, Andy. If the message of most Hollywood entertainment is, “You can be anything you dream of being,” the message of Toy Story is, “No, you can’t.”

Disney/Pixar

Disney/Pixar‘Falling with style’

It’s an amazingly mature message for a live-action film, let alone an animated one, but Toy Story set the Pixar trend for cartoons about adults, not children. In 1995, this was pioneering in itself. Fairy-tale princesses aside, the central characters in the most beloved Disney cartoons were and are pre-teens: Pinocchio, Dumbo, Bambi, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, Mowgli in The Jungle Book, Simba in The Lion King (which came out the year before Toy Story).

There are adults in these films, too, but the likes of Jiminy Cricket and Baloo the Bear are sidekicks and teachers; the protagonists are the youngsters they cherish. Toy Story upended that tradition. We barely see Andy, the owner of Buzz and the others, and when we do he looks like a monstrous giant alien. The main characters, the toys, are essentially his parents: harried adults who want nothing more than to please him, even while knowing that he will soon grow up and leave them behind. The genius of John Lasseter, the director of Toy Story and the chief creative officer of Pixar, is to enchant millions of children with films about how difficult and unrewarding their mums’ and dads’ lives are.

Disney/Pixar

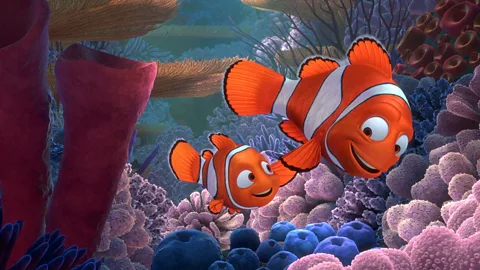

Disney/PixarThe theme is at its most poignant in Toy Story and its two heart-wrenching sequels, but it crops up elsewhere in the company’s canon. Finding Nemo is built on the anxieties of Nemo’s father, a widower packing his son off to school. In Monsters, Inc., Sulley and Mike are regular Joes who clock into work in a factory every morning, while the child in the film, Boo, is a problem they have to deal with. In Up, Carl Fredricksen is an embittered widower who never managed to go on the globe-trotting adventures that he and his wife always planned; and he, too, is landed with a small child to look after.

And in The Incredibles, Mr Incredible is forced to abandon his crime-fighting exploits and get an office job. It says a lot about the Pixar mindset that the one character in The Incredibles who has tried to fulfil his childhood dreams is Syndrome, the psychotic villain – and he ends up being sucked into a jet engine. His mistake, as Buzz could have told him, was thinking that he could fly, whereas the best we can hope for is “falling with style”.

Disney/Pixar

Disney/PixarPixar’s imminent release, The Good Dinosaur, may be its first to turn away from disappointed adults: its hero is a boy, albeit a boy dinosaur. But the company’s other 2015 film, Inside Out, sticks to its usual perspective. On one level, Inside Out is the coming-of-age story of an 11-year-old girl, Riley, who explores the wider world, like Bambi and Pinocchio before her. But, unlike Bambi or Pinocchio, Riley herself is pushed into the background.

The characters in the foreground are parental figures once again: anthropomorphised emotions who care desperately for an oblivious child. And what are those emotions? According to Inside Out, each of us is ruled by five dominant feelings, and while one of them is Joy, the other four are Sadness, Fear, Anger and Disgust. Ingmar Bergman, you imagine, might have deemed this take on the human psyche to be a bit on the gloomy side.

Still, Bergman and any other writer-director would have been proud of the film’s ultimate lesson: that everyone is miserable some of the time, and that that’s OK. That’s what adulthood is all about. Many viewers had tears in their eyes when Riley learnt that lesson in Inside Out. But poor Buzz Lightyear learnt it in Toy Story 20 years ago.