The eerie historical visions that predict the apocalypse

The Augsburg Book of Miraculous Signs reveals a 16th Century society gripped by anxieties that we can relate to in the 21st Century, writes Rebecca Laurence.

Giant locusts swarm around a jagged aquamarine mountain. Great whales and strange beasts flounder amid stormy seas. Inky skies rain hailstones and blood. These bizarre and terrifying visions are found in the Augsburg Book of Miraculous Signs, also called the Book of Miracles. It is a beautifully illustrated manuscript created in the German city in the mid-16th Century but only recently discovered and now collected in a new edition, by Till-Holger Borchert and Joshua P Waterman.

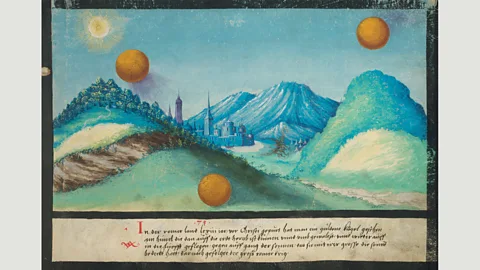

Golden balls

The Book of Miracles / Taschen

The Book of Miracles / Taschen“I that when I first saw the images in the flesh,” Till-Holger Borchert tells BBC Culture, “I was awestruck by the very touching combination of simplicity and beauty in systematically depicting catastrophes of all times.”

“These stunningly vivid pictures must certainly have imparted to those readers first seeing them a sense of awe at the progression of disasters and wonders from the beginning of history to the end of time, as then understood,” writes Waterman. The first half of the book concerns the Old Testament, while the second spans from antiquity through to the mid 1500s, when the book was produced. It ends with stories from the Book of Revelation.

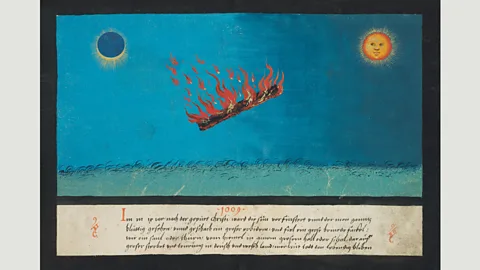

Feel the burn

The Book of Miracles / Taschen

The Book of Miracles / TaschenEach image, such as 1009 - Burning torch, is accompanied by a caption that leaves no doubt as to its grim message: “In the year AD 1009, the sun went dark and the moon was seen all bloodred and a great earthquake struck and there fell from the sky with a loud and crashing noise a huge burning torch like a column or a tower. This was followed by the death of many people and famine throughout and Italy. More people died than remained alive.”

By drawing from ancient, biblical and contemporary traditions of prophecy in roughly chronological order, The Book of Miracles follows an established structure similar to other contemporary books of wonders. It’s a tradition that highlights the period’s ordering of history through the prism of apocalyptic signs and visions. “When studying this one-of-a-kind series of illustrations,” Waterman says, “it’s important to keep in mind the structuring principle of Christian world history.”

“The 16th Century’s obsession with miraculous signs has its primary origin in religion, specifically in the upheavals of the Protestant Reformation,” he notes. Borchert agrees. “The late medieval councils had left Christendom in an insecure state, and the Reformation tried to fill the void,” he explains. “There was a general sense and urgency concerning the afterlife and the best way to secure one’s fate.” A widespread and imminent sense of disaster “created a sphere of anxiety in which those miraculous signs played an important role.”

The ‘Papal Ass’

The Book of Miracles / Taschen

The Book of Miracles / TaschenMany of the book’s images, such as the 1496 Tiber monster, have their origins in contemporary folklore: a monster was said to have been found in Rome on the banks of the Tiber after a flood of 1496. But, Waterman says the beast is also “the prime example” of phenomena that he says were “put to propagandistic or polemical use.” In 1523, Martin Luther and his colleague Philipp Melanchthon published a pamphlet in which they depicted the donkey-like creature as the ‘Papal Ass’, to represent the corruption of the Roman Catholic church.

“Scholarship has identified a strong apocalyptic slant in the thinking of Martin Luther and in early Lutheranism in general” Waterman explains, “fueled in part by a belief that the antichrist was present on earth in the person of the Pope.”

But although apocalyptic Lutheranism helps to place The Augsburg Book of Miracles firmly in its time, Luther’s polemical version of the Tiber monster story, Waterman explains, is entirely absent from the document. “Augsburg was a free imperial city, thus directly subordinate to the Holy Roman Emperor… For that reason, anti-Catholic polemics were in no way advantageous to Augsburg’s elites.”

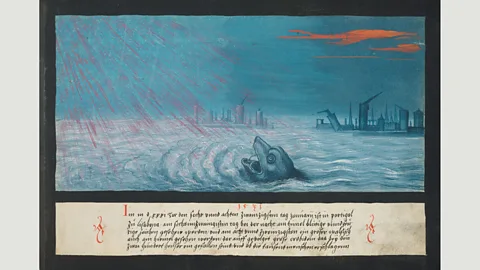

The Lisbon whale

The Book of Miracles / Taschen

The Book of Miracles / Taschen“In the year 1531, on the twentysixth and the twentyeighth of January, bloody and fiery signs were seen at night in the sky in Lisbon in Portugal on the twentysixth day and then on the twentyeighth a great whale was seen in the sky. This was followed by great earthquakes, so that about two hundred houses collapsed and more than a thousand people were killed.”

The ‘Lisbon whale’ demonstrates how stories were disseminated across Europe through media including letters and pamphlets, in what Waterman describes as “the earliest forms of modern news networks,” that ran along existing trade routes. He cites the ‘Fugger newsletters’ (Fuggerzeitungen), named after the Augbsurg-based Fugger family, as the prime example of “handwritten newspapers with reports of noteworthy events in Europe and abroad, including disasters and miraculous phenomena.” The sighting of the Lisbon whale, which was followed by several disasters, is one such story where the news was first transmitted by letter and then into print and illustrated media, including the Augsburg Book of Miracles.

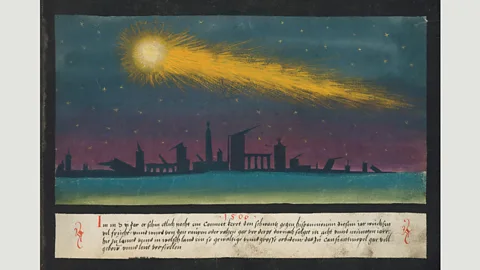

Celestial creatures

The Book of Miracles / Taschen

The Book of Miracles / Taschen“In the year 1506, a comet appeared for several nights and turned its tail towards Spain. In this year, a lot of fruit grew and was completely destroyed by caterpillars or rats. This was followed eight and nine years later, in this country and in Italy, by an earthquake, so great and violent that in Constantinople a great many buildings were knocked down and people perished.”

A contemporary preoccupation with astrological prophecy helps to explain why documents such as the Book of Miracles abound with suns and moons, and particularly comets, which were in antiquity considered harbingers of doom. “Authors such as Johannes Virdung von Haßfurt (1463–1538/39) published yearly predictions of world affairs based on sightings of comets and conjunctions of celestial bodies,” writes Waterman, and he notes that along with a “treatise” on the subject published around 1587 in Flanders, the Augsburg Book of Miracles represents the largest early collection of comet pictures.

The comet images in the Book of Miracles often appear accompanied by natural disasters such as earthquakes, floods and plagues which Waterman explains were all “understood as part of a continuum of divine omens that foretold the coming apocalypse and called upon humanity to do penance for their sins.”

All hail!

The Book of Miracles / Taschen

The Book of Miracles / Taschen“In AD 1552, on May 17, such a terrible storm with hail descended on Dordrecht in Holland, that the people thought the Day of Judgement was coming. And it lasted about half an hour. Several of the stones weighed up to a few pounds and 8 lot. And where they fell, they gave a frightful stench.”

The hailstorm that visited the town of Dordrecht in 1552 is the most recent of the events noted in the Augsburg Book of Miracles. The illustrations of violent hail and snowstorms are considered some of the earliest depictions of weather in German art.

“It was not uncommon for extreme meteorological phenomena such as hail, snow and ice to devastate crops and lead to famine and epidemics in their own right,” writes Waterman. It is therefore understandable that these wild and devastating natural disasters would be linked with the apocalyptic consciousness of the era.

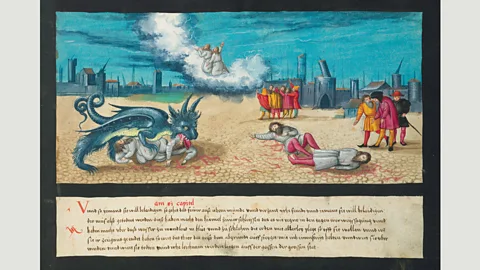

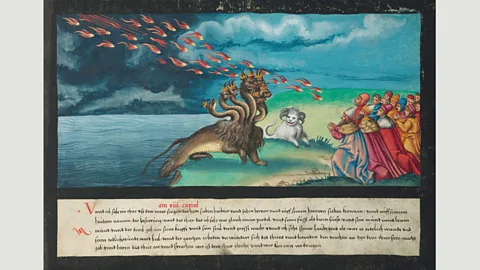

Fantastic beasts

The Book of Miracles / Taschen

The Book of Miracles / TaschenThe final section of the book, inspired by the prophecies of the Book of Revelation, is to Waterman, “a clear example of how wondrous phenomena fit within a comprehensive ordering scheme of world history, understood as a progression from God’s act of creation to the second coming of Jesus Christ.”

The Augsburg Book of Miracles is a fascinating glimpse into an atmosphere of superstition and apocalyptic prophecy. But rather than dismiss these views as bizarre medieval preoccupations, Waterman argues that “it’s easy empathise with the 16th Century’s efforts to understand strange, inexplicable, or disastrous events in the world, even if our modern understanding is drastically different.”

Age of anxiety

The Book of Miracles / Taschen

The Book of Miracles / TaschenAnd, in that society’s “sphere of anxiety”, Borchert sees some parallels with today, in that “every extreme weather phenomenon is hailed in news as proof of climate change and these days, every attack everywhere is almost instantly linked to terrorism.”

Yet this concern with weather and natural phenomena provides a more concerning link between the mid-1500s and today, Waterman says. “Thinking about environmental catastrophes back then and now, one becomes aware of a cruel irony: whereas human sin was once blamed for floods, storms, and droughts, only to have been replaced by scientific explanations after the Enlightenment, we have now, with global warming, come full circle.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.