Mondrian: The joy of being square

Alamy

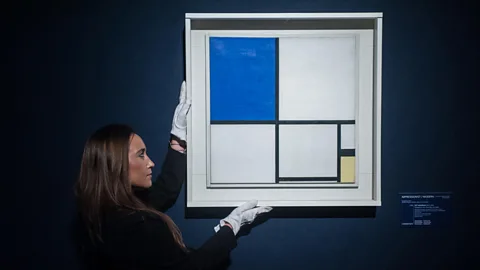

AlamyPiet Mondrian’s primary coloured geometric compositions say much about modern life, writes Alastair Sooke.

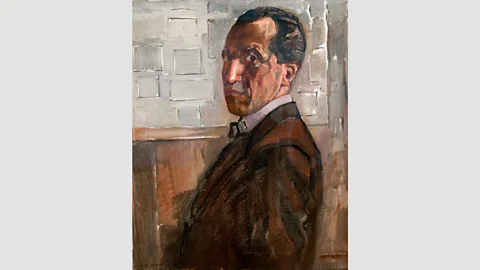

“Before you start to think about Mondrian’s paintings,” says the Dutch artist’s biographer Hans Janssen, of the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague, “you have to realise that he was born, in 1872, by candlelight in Amersfoort, a backward, economically undeveloped town in Utrecht. And he died, aged 71, beneath fluorescent lights, on the 3th6 floor of a skyscraper in New York. That’s an enormous leap, from the 19th into the 20th Century – and I think it’s very telling for the artist.”

We are standing in The Discovery of Mondrian, the Gemeentemuseum’s major new survey of the work of Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), which consists of around 300 paintings and drawings. It is the first time that every work by the artist in the museum’s collection has been shown simultaneously.

And, most likely, it will force anyone who thinks they know Mondrian, as a rational, rigorous painter of crisscrossing black grids embellished with blocks of primary colours, to think again.

Alamy

AlamyFor here, it is apparent, is an artist who went through many stylistic phases, as his paintings evolved from landscapes and still lifes that looked backwards, at time-honoured Dutch traditions, to the scintillating geometric canvases for which he remains best known today.

And Janssen’s point is that, while Mondrian’s well-known grids may seem simple and straightforward, it took him many years of experimentation and hard work before he was ready to produce them. Moreover, he did so, in part, in response to the great cities where he lived – Amsterdam, Paris, London, New York – and the dramatic forces that he sensed convulsing Western society within them.

Expanding horizons

Born in Amersfoort to a strict Calvinist family, with a heaster and amateur artist for a father, Mondrian grew up in Winterswijk, a small town to the east of the Netherlands, where the family moved in 1880. Keen to become an artist, he travelled to Amsterdam, aged 20, to study at the Academy of Fine Arts.

“In the early work that he produced, from his years in Winterswijk onwards,” says Janssen, “you can still see, let’s say, the candlelight: ie that Dutch tradition of realism, stretching back to the 17th Century. Even in Amsterdam, there was still a very conservative, closed-windows mentality.” The influence of historical Dutch art is obvious in Mondrian’s early landscapes, which do not prefigure his famous grid paintings of the ‘20s and beyond.

Alamy

AlamyAt the same time, Amsterdam encouraged Mondrian to expand his horizons. He fraternized in cafes with intellectuals and other artists, including the Dutch-Indonesian painter Jan Toorop, who introduced him to international art movements, such as Symbolism. Mondrian also indulged his love of dancing, and spent some of the money that he earned from sales of his landscapes and commissioned portraits on fashionable clothes: throughout his life, he was impeccably and elegantly dressed.

By 1909, he felt sufficiently self-confident to depart radically from 19th Century traditions – as witnessed by the way he transformed his studio. He got rid of some old-fashioned furniture, as well as several fusty carpets and drapes, and painted the walls bright white. For the rest of his life, Mondrian always arranged his working environment sparsely and meticulously, in a way that chimed with his abstract paintings – as journalists who came to interview him often noticed.

Alamy

AlamyThe most dramatic breakthrough in his art, though, was precipitated three years later, in 1912, when Mondrian, aged 39, moved to Paris. At that time, the French metropolis was the world capital of progressive art.

Although, to begin with, Mondrian’s best friends in Paris were other Dutch artists, he soon widened his circle, and became aware of aesthetic developments such as Cubism. Indeed, an exhibition held the previous year in Amsterdam containing works by Picasso and Braque had initially prompted Mondrian to consider heading for Paris.

Arriving in Paris, he felt excitement. “In his first week, he wrote a postcard to a girlfriend in Amsterdam in which he said, ‘You can so wonderfully be yourself here,’” says Janssen. “Which means that in a big city, you can lose yourself. There’s no need to show off – you can simply do your thing and be happy.”

Bright lights, big city

In 1913, Mondrian enjoyed success at the annual Parisian Salon des Independants, when one of his Cubist-inspired canvases received praise from the French poet, art critic and friend of Picasso, Guillaume Apollinaire. The following year, Mondrian created his first completely abstract paintings. Abandoning figuration altogether was an immense step.

Alamy

AlamyWhen the World War One broke out, Mondrian was back in the Netherlands, where he was spending the summer. Because his homeland remained neutral during the war, he decided it would be sensible to stay put. But it is a sign of how much Paris meant to him that, as soon as he could, once the war was over, he returned there by train in 1919 – and based himself in the French capital for the next 19 years. This period coincided with the heyday of his career, when he invented and expanded the timeless vocabulary of his visionary new visual language of geometric abstraction.

According to Janssen, other aspects of Paris, beyond the sphere of visual art, also had a decisive impact on Mondrian. “Mondrian moved to Paris because he wanted to be in touch with modern culture,” Janssen explains. “Not only within the visual arts, but also in a broader sense. Take dancing, for instance. Foremost among what he encountered in Paris was modern black American culture: early jazz and dancing – the two-step and the foxtrot. And he was always there when new things happened: when Josephine Baker made her first appearance in Paris, he was there.”

Janssen believes that there is a profound relationship between dancing and Mondrian’s art: “When you dance, reality can feel heightened. And that’s what Mondrian was searching for in his paintings: a heightened experience of reality.” Certainly, his abstract paintings have a sure grasp of visual rhythm.

Alamy

AlamyIn the late ‘30s, Mondrian’s life changed dramatically again, when he moved to London. Conscious that his work had been included in the infamous Degenerate Art exhibition organised by the Nazis in Munich in 1937, Mondrian felt concerned: “If the Germans seized Paris, he would be one of the first to be caught, so he couldn’t stay,” Janssen says. As a result, in September 1938, he boarded a boat bound for London. There, he hoped, he could rely on friends, as well as a decent market for his work. Guided by the artist Ben Nicholson, he settled in Hampstead, to the north of the city, where several other significant European artists, such as Naum Gabo and Kurt Schwitters, had also fled.

Mondrian spent less than two years in Hampstead – Janssen refers to this period as an “interlude”, before the “final act” of his life, in New York. Yet, while leafy Hampstead felt much quieter than Paris, Mondrian still felt excited when he did encounter striking examples of modernity, such as London’s Underground escalators, which, he wrote, dwarfed those in the Parisian Metro. London also offered Mondrian an opportunity to consolidate his reputation as an internationally significant master of abstract art.

Circles and squares

The outbreak of the World War Two induced Mondrian’s departure from London – indeed, in 1940, shortly after he had obtained his exit visa, a block of flats opposite his house in Hampstead was destroyed, during the Blitz. That autumn, he set sail from the Liverpool on a Cunard ocean liner for New York, where he spent his last years.

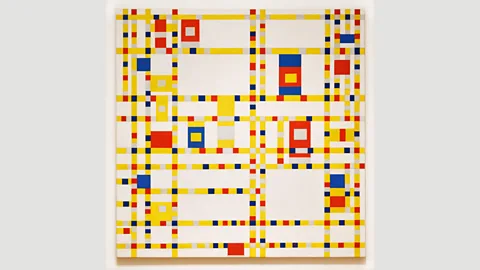

“Paris was busy,” Janssen says, “but New York was over the top.” Mondrian found himself revitalised by New York’s energy. The solid black lines of his earlier grids disappeared, and were replaced by broken-up, brighter structures, made of tiny pulses of pure colour. “With these ‘insertions’, he was trying to catch the rhythm of the new, utterly modern life he encountered there,” Janssen says.

Moreover, Mondrian’s ion for black American music, which had been ignited in Paris, became more intense, as he attended concerts by jazz musicians such as Duke Ellington. “I have a hypothesis,” Janssen tells me, “that he must have talked to a very young Thelonious Monk.”

Alamy

AlamyThe influence of the dynamic, syncopated rhythms that he heard in New York’s nightclubs is evident in Mondrian’s late, great compositions Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942-43), now in the collection of the city’s Museum of Modern Art, and the Gemeentemuseum’s unfinished Victory Boogie Woogie, the only painting that Mondrian worked on during the final year of his life.

Ultimately, the show at the Gemeentemuseum suggests that Mondrian wasn’t, as people often assume, a monk-like recluse, who devoted his life to abstract paintings with no relation to the real world. Rather, throughout his career, he engaged with, and fed off, aspects of modernity that he encountered in the cities where he lived. He loved music and clothes, always kept up with the latest developments in popular culture, including Disney cartoons, and had a vivacious love life.

Alamy

AlamyIn other words, he channelled the volatile energies that he sensed swirling through Western culture during the first half of the 20th Century – and he wasn’t afraid to let people know it.

In 1930, the American sculptor Alexander Calder, the inventor of the mobile, or moving sculpture, visited Mondrian in his studio in Paris. Janssen relates what happened: “Calder said to Mondrian, ‘Maybe you should take all these red, yellow and blue elements off the canvas and let them hang in the air, so they can move.’ Mondrian looked at him, and said: ‘Well, I think my paintings are fast enough already.’” Janssen pauses, before continuing: “And that really is the case: if you take the time to look properly at Mondrian’s [abstract] paintings, a world opens up.”

Alastair Sooke is art critic and columnist of the Daily Telegraph.