What Ridley Scott’s Alien can tell us about office life

Alamy

AlamyIt’s the 40th anniversary of the ground-breaking sci-fi. HR Giger’s nightmarish demon aside, the 1979 film is about a group of interstellar wage slaves doing ordinary, unglamorous jobs, writes Nicholas Barber.

Forty years ago, a little-known director and a little-known cast made a small-scale slasher movie set on a spaceship. It was a masterpiece. Ridley Scott’s Alien would go on to spawn three sequels, two prequels and two Alien v Predator mash-ups, not to mention a slew of comics and video games. But even after all this time, and all those spin-offs, the first film is unique.

A significant factor, naturally, is the title character: the sleekly nightmarish biomechanical demon designed by HR Giger. But another, under-rated, ingredient is everyone in the film who is not an alien. While James Cameron’s sequel revolved around a squad of hard-bitten marines, Scott’s 1979 original features ordinary, unglamorous people doing what are, for them, ordinary, unglamorous jobs. We never hear their full names, and they never talk about their past experiences or their future plans. Nonetheless, we get to know all seven of them, which is one reason why their deaths hit us with the force of a chest-bursting xenomorph.

Alien was greenlit by 20th Century Fox after Star Wars proved just how lucrative science-fiction could be in 1977. The two films aren’t wholly different, either. Han Solo, a scruffy, self-centred mercenary, was one of sci-fi cinema’s first great working-class heroes, and his battered, lived-in spacecraft inspired Scott. “[Star Wars] influenced me when I did Alien,” he said later. “I thought I better push it a lot further, make [the aesthetic] feel a lot like truck driving.”

Alamy

AlamyAnother influence was John Carpenter’s Dark Star, a low-budget hippy pastiche of 2001: A Space Odyssey, co-starring and co-written by the main screenwriter of Alien, Dan O’Bannon. Released in 1974, it too made a point of having a group of dishevelled and not particularly noble characters. But it was Alien, more than any previous film, which showed just how effective it could be to send a bunch of average joes into space rather than pirates and princesses.

Alamy

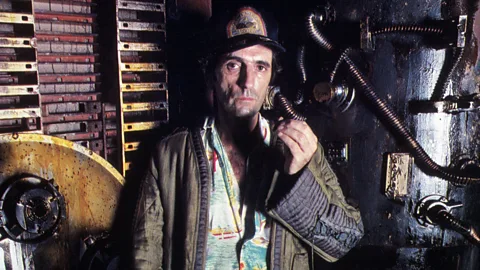

AlamyThe sheer normality of these interstellar wage slaves is conveyed before we even see them. At the start of the film, the crew of the Nostromo, a “commercial towing vehicle”, are snoozing in their suspended animation pods, but one of them has left a plastic drinking-bird ornament bobbing away on a table, and there is a coffee cup on a dashboard. Then, when the ship’s onboard computer wakes them, they don’t slip into form-fitting Starfleet uniforms and hurry to their posts: they shrug on their shapeless overalls, and then sit around eating and smoking while two blue-collar engineers, Parker (Yaphet Kotto) and Brett (Harry Dean Stanton), grouse about “the bonus situation”. And when they learn that the computer has picked up what seems to be a distress signal from a nearby moon, they don’t investigate because they want to rescue someone: they do so because they’re forced to, “on penalty of total forfeiture of shares”.

Working 9 to 5

The investigation ends badly, of course. The closest thing that Alien has to a conventional hero is Kane (John Hurt, Bafta-nominated for his performance), who offers to explore the hulking spaceship they discover on the stormy lunar surface, and is rewarded by having a spider-like parasite clamped to his face.

Alamy

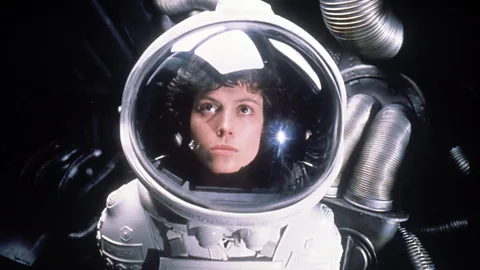

AlamySigourney Weaver’s redoubtable warrant officer, Ripley, refuses to let him back into the Nostromo’s shuttle. “If we break quarantine, we could all die,” she tells her fuming captain, Dallas (Tom Skerritt) – and she’s more or less right. But she is immediately over-ruled by Ash (Ian Holm), the science officer (and, spoiler alert, robot), who opens the airlock, thus endangering the entire crew. Not that he believes himself to be at fault. “I do take my responsibilities as seriously as you do, you know,” he mutters to Ripley. “You do your job and let me do mine. Yes?”

Alamy

AlamyIt may have been an accident that Ripley ended up as a woman – O’Bannon’s script didn’t specify the characters’ genders – but the fact that she did, and that she is being patronised by a male colleague, gives their argument an extra frisson. (And maybe there is some justice in – spoiler alert, again – Ash’s ultimate fate as a puddle of melted plastic and milky goo, while Ripley makes it out of the Nostromo in one piece.) There is a further frisson when Ripley complains to Dallas about Ash’s reckless behaviour, only for Dallas to growl, with a condescending “my dear”, that it’s not his problem, before changing the subject and stomping off in a huff. In short, Ripley puts up with a lot of mansplaining, 30 years before the term was coined.

It’s exchanges like these two that make the film so believable – and so recognisable. Look past the perfectly realised futuristic setting and you see an employee who gets on everyone’s nerves by citing the company’s rules; a ive-aggressive man who thinks he knows better; a boss who is too tired and lazy to sort out the dispute; two other colleagues who don’t care about much except their pay packets; another (Veronica Cartwright) who goes to pieces at the first sign of trouble; and another who volunteers for all the difficult jobs, only to find that no good deed goes unpunished. As strange and terrifying as Alien may be, you couldn’t ask for a sharper snapshot of working life.

Alamy

AlamyOne of its funniest moments is when the shuttle craft is damaged on impact with the moon, and the captain radios the two engineers to ask how long repairs will take. “Seventeen hours, tell him,” mumbles Brett in the engine room. “At least 25 hours,” says Parker into the radio, speaking for anyone who’s ever had to meet a deadline. But there are countless moments like this one, countless throwaway reminders that, as far as the characters are concerned, this isn’t a fantastic adventure, it’s just another day at the office.

Alien, it is often said, is a Freudian film about sex and reproduction and the fears that come with them. But it’s also about the camaraderie and irritation that come with being stuck in a confined space with your fellow staff . It’s about the pecking order, the salary disputes, the grumblings about canteen food, the remarks about who is sitting in who’s favourite chair. And it’s about the coffee – always the coffee. “You had Yaphet Kotto and Harry Dean Stanton, a sort of double act below decks,” Scott told Bafta in 2018. “And they give it that working class problem.”

No other horror or science-fiction film has captured the humdrum reality of doing a day’s work for a day’s pay with such accuracy. For that matter, perhaps no film of any genre has. There may be sitcoms that depict these everyday frustrations and interactions as deftly as Alien does. But in the cinema? The most authentic ever film about earning a living could well be the one with a giant, slimy, acid-blooded extra-terrestrial monster.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.