Spike Lee’s masterpiece about racism in the US

Alamy

AlamyBack in 2000, Spike Lee’s Bamboozled was a flop in cinemas. Yet this explosive satire has come to be seen as a masterpiece, skewering racial prejudice, writes Kaleem Aftab.

Spike Lee’s 14th feature film, Bamboozled, was released on 6 October, 2000, in the United States. It was a flop. “To me, the definition of a cult classic is a film that nobody went to see when it came out,” Lee bellows down the phone from his home in New York with a hearty laugh. Made on a $10 million budget, Bamboozled earned back less than $2.5 million worldwide.

Warning: This article contains strong language that might cause offence.

More like this:

Lee saw Bamboozled as a way to mark the 100th anniversary of cinema and 50 years of TV. A time for celebration for many. Not for Lee. He wanted to look at the history from another perspective: “I felt it would be a good time to look at how [these art forms] treated the depiction of black people.” Not good, is the short answer. “It’s the exploration of how [they have] dehumanised human beings.”

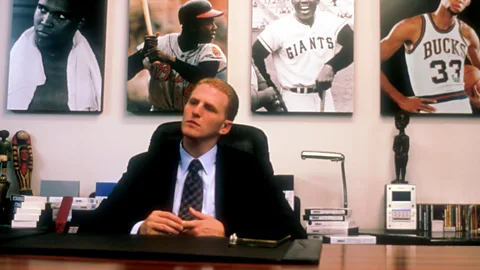

Harvard-educated Pierre Delacroix (Damon Wayans) is the only black executive working at TV network CNS. Speaking with an affected accent, designed to make him sound like a WASP, Delacroix delivers a definition of satire, setting the tone for this film made in the tradition of Sidney Lumet’s Network (1976) and Elia Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd (1957). Delacroix entered TV with the foolhardy ambition and hope that he could change the stereotyping and racial tropes that litter everything he watches. The film shows the impossibility of achieving this in a world of TV and cinema that is institutionally racist.

Alamy

AlamyHis boss, Thomas Dunwitty (Michael Rapaport), is part of the problem. Dunwitty thinks it’s hip to mimic African American vernacular and liberally use the n-word. He feels that he has permission to do so because he married a person of colour and has two mixed-race children. Ratings are falling at the station and Dunwitty believes that the only way to stop the rot is by attracting an urban audience to the station. He turns to the solitary black man in the building for ideas but rejects every suggestion with positive messages about black people.

Delacroix comes up with an idea that he and his assistant Sloan Hopkins (Jada Pinkett Smith) believe is sure to get him fired: Mantan’s New Millennium Minstrel Show. The show features every single racial stereotype imaginable. He even goes so far as to employ black homeless tap-dancing street performers Manray (Savion Glover) and Womack (Tommy Davidson), putting them in blackface and rechristening them Mantan and Sleep ‘n Eat. But rather than being the end of his career, the show is a huge success. Delacroix laps up the acclaim, forgetting his reservations about similar material in the past and earning the criticism of his parents and Sloan.

Alamy

AlamyThe show may please the masses, but many of the African Americans that it is lampooning are furious. The Mau Maus, a group of black militant activists, decide to take retaliatory action against the racism of CNS by kidnapping the show’s star and executing him live on the Internet.

Tarnished silver screen

Lee takes no prisoners when firing bullets at American cinematic history. The film ends with a montage sequence showing the use of blackface and racist tropes throughout the history of American audio-visual entertainment. Lee calls it “one of the best scenes I have ever done”, even though he also feels that it was part of the reason why the film was dismissed at the time of its release. “Because those images are so hurtful. Who wants to see Judy Garland, Bing Crosby and Mickey Rooney in blackface? We wanted to use a clip of Bugs Bunny in blackface, but Warner Brothers wouldn’t give us clearance to use it.”

American critic Roger Ebert condemned Bamboozled by writing, “I think his fundamental miscalculation was to use blackface itself. He overshoots the mark. Blackface is so blatant, so wounding, so highly charged, that it obscures any point being made by the person wearing it.” While Anthony Lane stated in The New Yorker, “Enough has changed for audiences to know blackface is ugly and unfunny.” Amy Taubin argued in the Village Voice that Lee had made “a justified but overly reductive attack on the television industry for its degrading representations of African Americans and on the audience that swallows the racist brew and begs for more”.

Alamy

AlamyIn between the mudslinging, some outliers argued that Lee had made something elevated. For example, Stephen Holden’s considered review in The New York Times claimed: “The nifty concept behind this dangerous free-for-all satire on race, television and black images in the media is demonically inspired and uncomfortably to the point.”

Part of the film’s ire is aimed at how media representation creates stereotypes and behaviours that normalise prejudices and have long-lasting effects and how even the community being subjugated can regurgitate these tropes, creating a new neo-minstrelsy. Lee explains, “I include black folks too [in my criticism and] they were dismissing the film too.”

The use of the n-word in Gangsta rap was, according to Lee, as terrible as the overuse of the term in the films of Quentin Tarantino, with whom the director had a long-running feud. Bamboozled highlights how Gangsta rap, fashion and advertising reinforce negative images.

Alamy

AlamyAlthough Lee was dealing with African Americans, he says the themes of the film affect all minorities. “The same film could have been done about the treatment of Native Americans on TV and film, Hispanics, women, gay people and Asian. It’s an exploration of how this art form was used to dehumanise human beings, which culminates in one of the best scenes that I’ve ever done.”

The filmmaker was crestfallen by the failure of Bamboozled at the time. “It was not a good feeling, I’m not going to lie,” re Lee. “First of all, any film I do, I hope it’s well-received by the audience. I don’t think an artist, whether an author, musician or filmmaker, can predict how the public is going to respond to their art. There are so many factors, especially with film – how much was the ad spend, and did it come out on the same day as Star Wars? – that has nothing to do with what you make.”

Lee is at pains to point out, “I was disappointed with the reaction, but I wasn’t disappointed with the film. There is a big difference. I knew this film was truthful. It is the film I wanted to make without lying about what happened.”

Alamy

AlamyThe New York director dusted himself off, and quickly moved on. “I would not have been able to amass the body of work that I have by letting someone stop me. So, after Bamboozled, I went onto the next film and the next film.”

I wrote a biography on the filmmaker, Spike Lee: That’s My Story and I’m Sticking To It, and when discussing the project in late 2002, the curious director sounded me out by asking what my favourite one of his films was. My response was Bamboozled, which I felt had been maligned unfairly. The film saw Lee tackle racism head-on for the first time since Do The Right Thing, and deciphering several levels of prejudice in striking and unique ways. It could only have been made by a film insider, privy to all the shenanigans at work designed to keep the cream at the top. It brought a big smile to the director’s face. He wondered whether I’d seen the film on DVD, as a few people had been discovering the film that way. I’d actually seen it at the Ritzy in Brixton, travelling miles from my home to get to one of the few cinemas with the foresight to show the film.

Becoming a cult classic

Bamboozled came and went and even the DVD was eventually hard to come by. It was a forgotten movie. The world, according to the critics, had moved on. Proof of that came with the election of President Barack Obama, a sure sign that the US was on its way to becoming post-race. Then several tragic incidents changed that perspective and highlighted how, rather than being a historical document, Bamboozled was a story of our times.

George Zimmerman shot dead 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Florida in 2012; his claim that he was acting in self-defence was accepted by a jury. His acquittal inspired waves of protest and activism. It was the spark that created the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013, campaigning against systematic racism towards black people. In 2014, after Eric Garner and Michael Brown were killed by police officers in separate incidents, Black Lives Matter organised national protests and the social media handle #BlackLivesMatter became part of the vernacular.

Following on from #BlackLivesMatter came #OscarsSoWhite, a social media campaign that forced the film industry to look at the composition of its gatekeepers, which accelerated in the aftermath of #MeToo. Suddenly Bamboozled didn’t seem like it was a film looking back at the past, but a first step in highlighting the problems that needed to be addressed for the entertainment industry to change.

Alamy

Alamy“Lee’s vision was not only necessary, it proved remarkably prescient,” wrote British writer Ashley Clark in an edited extract from his book Facing Blackness: Media and Minstrelsy in Spike Lee’s Bamboozled published in the Guardian in 2015. “Bamboozled’s trenchant commentary on the importance, complexity and lasting effects of media representation could hardly feel more urgent. Each time an unarmed black person is killed, then hurriedly repositioned in death as a thug, a brute, or a layabout by mainstream media outlets… we are seeing the perpetuation of old anti-black stereotypes, forged in the crucible of mass American art, reconfigured for our time.”

Critical opinion on Bamboozled began to change. In Indiewire, Jordan Ruimy argued, “Lee’s film is as relevant as ever, dealing with an African American’s frustration with a blindly racist country.” Lee says of the change in opinion, “Many years later it’s rediscovered and so that’s a good feeling. It’s not a thing like ‘Yeah motherfuckers I told you back then’. That’s not the attitude that I had. I’m just happy that people are rediscovering the film. Also, people see this film who weren’t even born when it came out. There is a new generation that wasn’t even around when the film came out.”

Now the film has been added to the Criterion Collection, a home entertainment label that has become synonymous with organising re-releases of only the best of cinema. According to Abbey Lustgarten, who produced the release for Criterion, “It [Bamboozled] has been long overdue for a reappraisal as a central work in Lee’s filmography. This was also a chance to do something the filmmaker had wanted, from a technical perspective. With newer restoration tools and access to original materials, we could address the challenging mix of DV and 16mm footage and make that contrast as distinct as Lee and his cinematographer Ellen Kuras had always imagined.”

The release has seen a wave of articles citing the importance and greatness of Lee’s film. David Fear argued in Rolling Stone, “At the turn of the century, it seemed like a crude attempt at sketch comedy. Twenty years later, the movie feels like a forgotten gem in Spike’s career, one whose spit-polish and reappraisal comes at the exact right moment.” Lee says, “I don’t think it’s a case of I’ve been vindicated because I knew what I did when I did it. It’s just that old cliché, better late than never.”

Love film and TV? BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.