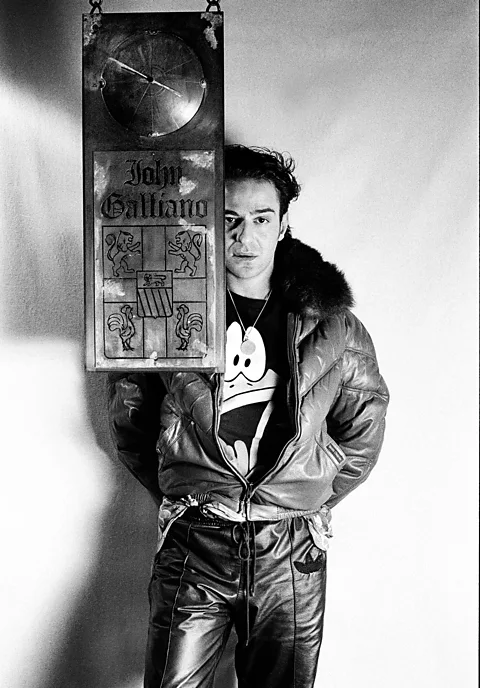

The dramatic rise-fall-and-rise of John Galliano

Derek Ridgers

Derek RidgersAs a new film High & Low looks back at John Galliano's lurid story, why can't fashion fans get over the "enfants terribles" Galliano and Alexander McQueen?

John Galliano's first major commercial show in 1985 ended in a model throwing fresh mackerel at the audience from the catwalk. Model Mimi Potworwska had bought the fish that morning to cook for dinner but decided in the heat of the moment to fling them into the crowd – narrowly missing grande dame of fashion Joan Burstein, the owner of prestigious boutique Browns (and one of Galliano's biggest patrons). The collection, titled The Ludic Game, ran various images and stories through the blender: London's pearly kings and queens meeting forest nymphs sprouting leaves from their heads, the overarching narrative inspired by Angela Carter's then-recently released novel Nights at the Circus (1984) with its cast of clowns and journalists, its protagonist a fin-de-siecle aerial performer called Fevvers who claims to have wings.

Barry Marsden

Barry MarsdenThe fish-throwing moment raises many questions – not least the refrigeration situation between morning market purchase and catwalk curtains up – but it was the perfect embodiment of the absurdist theatricality that would make Galliano's name. This show is referenced early on in Kevin Macdonald's new documentary High & Low: John Galliano, charting the designer's ascendancy to the highest levels of fashion glory before his abrupt fall from grace when he was recorded making drunken racist and anti-Semitic remarks in the Café la Perle in Paris in 2011.

The documentary is a well-observed portrait of a child who sought refuge in his imagination from a difficult domestic life, and a man whose New Romantic club kid days and smash-and-grab approach to history, art, and world culture took him all the way from fashion college to contracts with Givenchy and Dior – where the models didn't fling mackerel but did emerge dressed as flowers, Egyptian queens and ancien regime empresses, playing at Princess and the Pea as they teetered on stacked mattresses or posing alongside enormous chairs like couture-clad Borrowers.

High & Low is simultaneously an effective retelling of Galliano's colourful life and work, a snapshot of a luxury industry experiencing rapid growth, and a frustrated meditation on redemption and contrition in the aftermath of the designer's alcoholic outbursts, for which he was eventually fined €6,000. In the present day, there is a curious mix of honesty and evasion to Galliano – the desire to tell all is at cross purposes with conflicting s of who received apologies when, and the designer's obvious discomfort in dwelling on the reasons for saying what he said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt's striking timing for the documentary's release. During January's couture season in Paris, the show that caused the biggest excitement was Maison Margiela, where Galliano marked a decade as creative director, having started in 2014 (as critic Robin Givhan quips in High and Low, "fashion has a very short memory"). It was an astonishing collection, harking back to Galliano shows of yore as models – made up like porcelain dolls – staggered and swayed down a gloomy catwalk, waists distorted by corsets and merkins peeping through their tulle. Inspired by the clandestine, candid work of Hungarian photographer Brassaï who photographed Paris and its inhabitants after dark, it was a sensation online and was hailed by the press as one of the most exciting shows in years. Alexander Fury at AnOther called it "a celebration of humanity, of individuality, of fashion as pure creative expression" while Cathy Horyn observed in The Cut that it "[left] most shows, however beautiful and well executed, in its dust."

It wasn't just the construction of the garments or the ingenuity of the hair and make-up that made it a hit. Rather, it was the sheer Galliano-ness: the combination of humour, assiduous craftsmanship, and tingling atmosphere that let the audience believe they weren't just at a trade show (which is essentially what a catwalk is) but party to a one-off drama. Fashion's claim to relevance, beyond selling us new stuff, has always been that it conjures a world of fantasy away from humdrum life, beckoning us through the looking glass into a land where beauty reigns and dress up can be transcendental. That promise has dulled in the past decade or so, leaving people hungry for shows and clothes that might make fashion feel magic again.

By again, I mean like in the 90s and early 00s: a fertile period in fashion history, where the showmanship of Thierry Mugler and Claude Montana and punk experimentations of Vivienne Westwood paved the way for an explosive new generation of designers including enfants terribles John Galliano and Lee Alexander McQueen. These young, working-class Londoners, both of whom studied at Central Saint Martins, were aesthetically polar but creatively parallel: their skills with the cutting scissors matched by an elasticity of imagination that transformed fashion into a stage capable of hosting extravagant fairy tales or, especially in McQueen's case, probing at the darkest fringes of history and human behaviour. When Galliano left Givenchy for Dior, the 27-year-old McQueen was his successor.

Getty Images/ Alamy

Getty Images/ AlamyThere is a strong sense of nostalgia for this era. It is more available to see than ever before, images and videos of catwalk shows and editorials scattering social media, while the rise in archival fashion on the red carpet has turned some of Galliano and McQueen's most famous designs into collector's pieces worth tens of thousands of pounds. What people yearn for, it seems, is the idea of fashion rising above its commercial tethers to become something more pulse-raising: part-art, part-theatre, part-childhood fantasy (or nightmare) writ large. They want clothes that aren't just made to be worn, but to provoke deep feeling – whether or not one can afford the price tag.

More like this:

The other fashion show that has caused the most consternation so far this year was Seán McGirr's debut collection at Alexander McQueen. He assumed the mantle from Sarah Burton, Lee McQueen's right-hand woman who became creative director after McQueen's death in 2010. For 13 years she took the label in a softer direction, maintaining McQueen's focus on tailoring and craft while producing clothes that Catherine, Princess of Wales, would more likely wear. It was announced last year that she was being replaced with Irish designer McGirr, incoming from JW Anderson.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen McGirr's first efforts for the brand were revealed in Paris the weekend before last, the response was intense – an online chorus crying out in horror about McQueen's legacy being "ruined". This was unduly histrionic. McGirr's collection, inspired, he said, by "damaged opulence" and "this sort of rough glamour of the East End," and drawing on earlier McQueen collections including spring/summer 95's The Birds, was by no means flawless. Its highlights – smashed mirror dresses, horse hoof shoes, sharp-shouldered trench coats fit for a cartoon villain – were undercut by various dud notes (the prints were a low point, and a series of steel moulded dresses felt too derivative of the rigid bodysuits done by Tom Ford and Schiaparelli.) It didn't yet possess McQueen's artistic flair or technical execution, but it was certainly spikier and more promising than Burton's fare – which in recent years featured endless variations on the same corseted silhouette.

Then and now

McQueen famously garnered bad press for various collections, from accusations of misogyny in his autumn/winter 95 Highland Rape collection, riffing on the legacy of the Scottish clearances, to a tepid response to his Givenchy debut the following year, Hilton Als reflecting the general mood when he wrote in the New Yorker that "the ladies of couture… were taken aback… by the sheer excess of youthful vitality and confusion parading before them in outrageous clothing."

Although it's relatively obvious to draw a parallel between this and McGirr's backlash, the truth is, there is no comparison. How could there be? The world in which McQueen and Galliano were operating in is vastly different to the world of fashion today – which is more creatively stagnant, and more profitable, than ever. We don't know how closely the corporate overlords are hovering on McGirr's shoulder, but if it's true that Burton was let go because of commercial reasons, then there will be an enormous pressure to deliver commercially – an aim that does not always dovetail with exuberant creativity.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 2011, the year that Galliano was fired from Dior, Vogue reported that revenue from its parent company LVMH had reached €23.7bn – thanks, in part, to profits at Dior. In 2023, LVMH reported that their revenue was €86.2bn. Even adjusting for inflation, it's a big leap, fuelled not only by continued growth at Dior and Louis Vuitton but also the 2021 acquisition of Tiffany & Co and the success of smaller labels like Spanish brand LOEWE, where Jonathan Anderson is creative director. LOEWE, in fact, is one of the few brands that seems to be successfully melding artistry and commercial growth (which may explain some of the more LOEWE-ish undertones in McGirr's collection, alongside his previous work at Anderson's namesake label).

When Galliano was fired from Dior, he said that he was buckling under demands made on him – producing up to 32 collections a year. This level of pressure and expectation contributed to his addiction problems, alongside the death of his friend and collaborator Steven Robinson. However, the industry's hunger for growth has only increased since then, becoming a bottomless maw demanding more clothes, more handbags, more viral moments, more clothes tailored to a global customer base. Perhaps what has changed is the tolerance for the kind of maverick genius that can produce great beauty and genuinely challenging work but may also wind up a liability. Many major fashion houses are now playing it safe, their creative directors either clangingly benign (Maria Grazia Chiuri at Dior, Virginie Viard at Chanel) or coming with in-built mass appeal (Pharrell at Louis Vuitton Men's). Other houses flash through creative directors at breakneck speed, keeping them in situ for a couple of years or even just seasons at a time before letting them go in search of newer, shinier names that might better please their shareholders.

A common refrain heard about McQueen and Galliano is that they were major inspirations for younger generations of designers who hoped to follow in their footsteps. They were seduced by the idea of fashion as the ultimate form of creative fusion: historic references and favourite paintings and weird preoccupations poured into fabric, resulting in something that could be worn but also made a statement that was more than the sum of its seams.

High & Low

High & LowFor many of them, now faced either with the difficulty of launching an independent label and keeping it afloat in a precarious market or attempting to scale up the luxury ladder to that top rung of creative director – a role that encomes design but really means helming the direction of a brand, with ever-narrower creative latitude and ever-larger decisions and pressures – it's understandable that they feel stranded in an alien world. Under such circumstances a retreat into the archives makes sense.

But there is a difference between taking inspiration and being reenvigorated, and finding oneself haunted by ghosts of decades gone by. Perhaps the truth is that fashion has had its golden age. But it will have no hope of a new one, whatever fresh form it takes, unless its com is set to the future. It is harder to move forward when constantly looking back over one shoulder, to find new horizons when stuck in the mud of the past.

High & Low: John Galliano is at cinemas and available to stream on MUBI now in the US and UK, and in Canada from 15 March.