Citizen Kane’s follow-up: The greatest sequel never made?

Getty Images

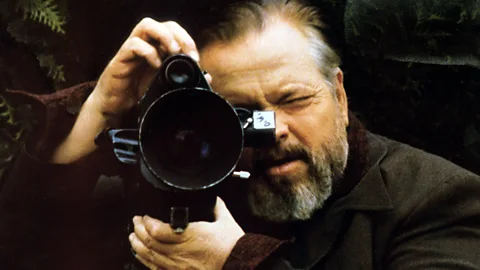

Getty ImagesIn honour of Orson Welles’ death 30 years ago, his friend film-maker Henry Jaglom tells the colourful story of their attempt to make a ‘bookend’ to the greatest American film.

One day in the early 1980s, at one of our weekly lunches at Ma Maison in Los Angeles, Orson seemed really defeated.

I had to tell him that one more attempt of ours to get financing for his King Lear film project had fallen through. This was not new. We had been trying to get him financing for several projects over the last few years, and though every potential backer

for the many films he proposed was more than happy to have lunch with him, one by one, they backed away from actually making a deal.

Welles’ career post-Kane could be considered spotty – despite several masterpieces, such as The Magnificent Ambersons, Chimes at Midnight, The Immortal Story, F For Fake – and I could now see that, indeed, none of the deep pockets drawn to Welles were willing any longer to invest in him. Welles found himself in the paradoxical position of being supremely honoured as "America’s greatest film-maker'' yet unable to get backing for any of his new projects. He wanted to do this wonderful adaptation of Isak Dinesen stories, The Dreamers. I went around to every studio with it, every producer, and I couldn’t get him financing.

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock PhotoSo I said, “Orson, they don’t want to do an adaptation. They don’t want to do something ‘old’. His concept for Lear was extraordinarily brilliant and unique and we had lined up some of the English-speaking world's greatest actors to work for nothing. We had formed a company – Weljag – to produce it and at the very last moment the money simply dropped out.

Inspiration strikes

"I'm cursed", said Orson. "I'm finished." "No, no, no,” I insisted. “They just keep telling me that they don't want to do something ‘old’, but I think I can sell you with a new movie, and a new script. Tell me some stories you've always wanted to do!” He looked down, entirely defeated. “No. I can’t write anymore, I’m no longer capable of writing. I simply can’t. I’ve tried, and it’s no dice. It’s gone, whatever that gift was.”

“You’re just giving yourself excuses,” I shouted at him one night. Just put something down on paper. Or just tell it to me; I’ll put it down on paper. Anything! Three pages of anything!”

“I can’t! I know what I can do now, I know what I can’t do!”

Then, three days later, the phone rang at 4 am. He shouted at me, “I don’t know what… you’re making me do this for. I can’t sleep, but I’ve written three-and-a-half pages. They’re terrible!”

AF archive/Alamy

AF archive/Alamy“Read them to me,” I insisted. Of course they were great. I mean, really great. “Write me three more tomorrow night.” The next day I got seven! In this way, day after day, week after week for the next three or four months, I got him to write this whole script. It was called The Big Brass Ring, and it was about an old political advisor to Franklin Roosevelt, a homosexual named Kimball Menaker. He’s mentored a young, Kennedy-esque senator from Texas with presidential ambitions named Blake Pellerin, who runs against Ronald Reagan and loses. Pellerin, wrote Welles, as if describing himself, “is a man who has within him the devil of self-destruction that lives in every genius… Like all great men he is never sure that he has chosen the right path in life. Even being president, he feels, may somehow not be right: ‘Should I be a monk? … Should I just… forget about everything else?’ That is what The Big Brass Ring is all about.” It was magnificent, and I was certain that others could not fail to agree.

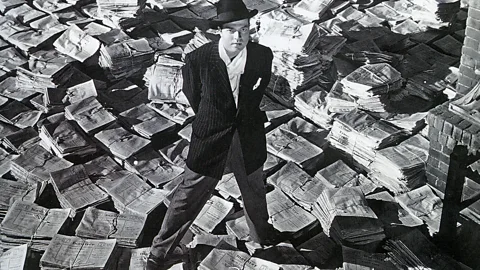

The Big Brass Ring was about America at the end of the century, the way Kane was about America at the beginning of the century. I couldn’t believe it – I had him write, essentially, a bookend to Kane. Now, I was sure the wallets would open. I told Orson, “You know, all the people I came up with and struggled side by side with have by now become the top stars and the key production and studio heads. I know them; they’re my friends. We were all unemployed together. They all worship you!” And I wasn't making it up. They had all, at one time or another, been crazy fans of Orson's films. Just like me.

The ‘Ring’ cycle

So, I went around to everybody, had lunch in every executive dining room, and I couldn’t get anyone to do it. No one! Every studio turned it down – after a wonderful lunch they had begged to have with Orson, of course, during which he would regale them and entertain them for hours with wonderful stories. He called it his "dancing bear act" and said, wearily, that that was really all they wanted from him now. I protested but, sadly, he was right. The times had changed. These people I came into the business with changed. Instead of talking about film-makers now, or about the movies being made, they were talking about grosses. Orson understood this. He said, “I expected the studios to turn me down. Why wouldn’t they? I’ve never made any money for them. Not one of my films made a profit. But what about the actors? Call the stars. They’ll never turn me down and that will force a studio to do it.”

So after I failed to get the studios to show even a glimmer of interest in The Big Brass Ring, I went to my old friend, independent producer Arnon Milchan, who backed and ed daring film artists, such as Terry Gilliam on Brazil. He agreed without hesitation to give Welles $8m and ‘final cut’, complete creative control, for the first time since Kane. But only “if I got one of six or seven A-list actors to agree to play Blake Pellerin.” I was certain we could do that and Orson was more than certain. So we celebrated, opened a huge bottle of Cristal, because the one thing Orson thought for certain was that actors would never betray him. He said, “I know actors.”

Speciality Films

Speciality FilmsBut apparently, here again, times had changed. Clint Eastwood turned down the film because it was “too left wing” for him. Robert Redford said sorry but he already had another political thriller lined up. Even Paul Newman wavered and finally ed. Burt Reynolds’s agent just said, “No.” Not a word from Reynolds himself. Orson said, “Burt Reynolds owes me so much. I wrote the foreword to a dumb book about him, and he didn’t have the guts to phone me himself and simply say, ‘It’s not for me’. Big money is the problem with all these stars today. When they get too rich, they behave badly.”

One by one each of these actors came up with reasons to bow out, including two of my close friends, Warren Beatty and Jack Nicholson. They both behaved well, but for different reasons they couldn’t do it. Warren was clear: he had just come off of his incredibly hectic schedule acting in and directing the brilliant Reds, which was a huge undertaking. In his inimitable fashion Warren said to me, “Oh God, tell Orson it’s like coming out of a whorehouse after being there all night [having sex] like crazy. You’re completely exhausted and you walk out into the sunlight and there is Marilyn Monroe with her arms stretched out. You’d love to, but you just can’t.”

Courtesy of Henry Jaglom

Courtesy of Henry JaglomThat explanation, of all of them, Orson understood best and smiled. “He sounds like me, once.” But Jack was another story. He said yes. He was the only one to say yes. “For Orson Welles, of course,” he said. But there was a ‘but’. A very big ‘but’, unfortunately. I told Orson the news, directly as Jack had told it to me: “I have good news and bad news, Orson. Jack said yes to The Big Brass Ring. He’d love to do it. He’d love to work with you. He loves the script.” Orson frowned at me: “And the bad news?” Me: “He won’t reduce his salary. He would for you, of course, but his managers and agents won’t let him. He gets many millions now per film, it took him years to get there, and it all will collapse if he does it for you at a quarter or a fifth of his price. His managers won’t let him do it. He is truly very disappointed and very sorry and sends his love.”

And with that, the sad story of The Big Brass Ring ended. Money had finally triumphed over art.

Henry Jaglom is an actor and film-maker, who directed A Safe Place, Eating and Festival in Cannes, among many other movies. He is also the author, with Peter Biskind, of My Lunches With Orson.