Anatomy of a murder story

Netflix

NetflixAs the latest addictive TV series sparks government petitions and hacktivist threats, BBC Culture looks at how groundbreaking true-crime stories have made their mark.

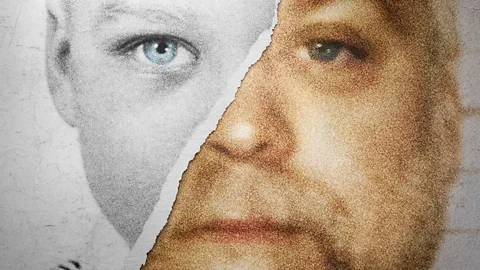

Slow panning shots over the landscape of rural America; roads slicing through flat farmland covered in snow: the latest TV binge-watching sensation has echoes of Fargo and True Detective. Yet there are no actors, and the events that unspool have not been scripted. Netflix’s Making a Murderer purports to tell a true story, following hit shows Serial and The Jinx in documenting perceived miscarriages of justice.

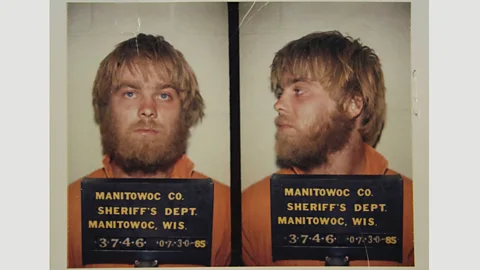

Steven Avery was exonerated in 2003. The Manitowoc, Wisconsin man had served 18 years for the sexual assault and attempted murder of a female jogger before fresh DNA evidence proved his innocence. Two years later, just after he had filed a $36m lawsuit against the local county, Avery was arrested for the murder of 25-year-old Teresa Halbach. In 2007, he and his nephew Brendan Dassey were convicted of Halbach's murder and sentenced to life in prison. Along the way, film-makers Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos recorded an of what Avery’s defence team argued were apparent wrongdoings by the police and prosecutors: forced confessions, conflicts of interest, planted evidence and, from the start, presumption of guilt.

A decade in the making, the 10-episode docies was only released on 18 December – but it has already created a furore. A Change.org petition asking for Avery to be pardoned attracted more than 300,000 signatures from people in 144 countries within a fortnight of its launch. Another, on the White House’s website, has met the 100,000 needed for an official government response. The imioned arguments of Avery’s defence lawyers have, according to The Daily Beast, turned them into “Atticus Finches for the millennial generation”. And hacktivist group Anonymous threatened to take justice into their own hands, claiming they would publish documents showing that evidence had been planted by police officers.

Amid the public outrage, there have been accusations of bias. Manitowoc County Sheriff Robert Hermann claims that footage was manipulated, while Ken Kratz, the former district attorney of neighbouring Calumet County – who prosecuted Avery – argues that Ricciardi and Demos omitted key evidence from the series. “You don't want to muddy up a perfectly good conspiracy movie with what actually happened,” he told People magazine.

A truth universally acknowledged by storytellers: what actually happened often gets in the way of a good narrative. True-crime stories have a particular kind of narrative, one that claims a special relationship with facts; some have even changed legal history. We’ve picked the features that mark out some of the most groundbreaking tales of real crimes.

Netflix

NetflixShow the other side

Making a Murderer is so popular not because it is sensationalist, but because it offers an alternative view to that recorded by the mainstream media at the time. Throughout the trial, press reporters are there, pacing a courtroom corridor as they recount a soundbite verdict (while they had prior access to the state's version of events, they weren't privy to the defence argument until it came to court). They deliver their news in breathless headlines and 24-hour coverage.

This series reveals another side. It tells us as much about the US legal system as about Avery’s testimony or the prosecutor’s claims. “We’re documentarians as well as storytellers, and part of the story that we sought to tell was the exploration of an experience of the accused in the American criminal justice system,” Ricciardi said in an interview on BBC Newsnight. “These are things that are happening in every county in this country,” Demos told The Daily Beast. “We hope that the dialogue gets beyond this case, and beyond Manitowoc County. I think that would be an opportunity squandered if the dialogue did not broaden to look at what the broader things going on here are.”

AP

APOffer psychological insight

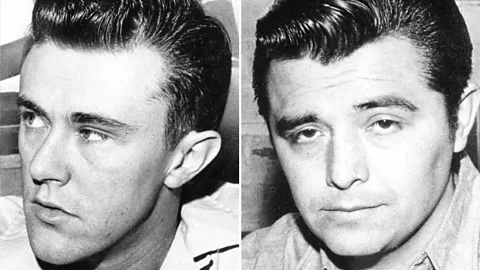

Subtitled ‘A True of a Multiple Murder and Its Consequences’, In Cold Blood has been credited with creating a new literary genre. Its author Truman Capote claimed to have written the first ‘non-fiction novel’ when it was published in 1966. The story about four of a family murdered in their Kansas farmhouse – and the arrest and subsequent execution of their killers – went on to become the second biggest-selling true crime story ever, as well as earning a place in the literary canon.

Yet some involved in the case have questioned its veracity. “I was under the impression that the book was going to be factual, and it was not; it was a fiction book,” said one of the agents at the Kansas Bureau of Investigation (KBI), Harold Nye, in George Plimpton’s book Truman Capote. His son Ronald – who is planning to publish a book based on his father’s case file – has said: “Capote had a fact here, and a fact there, and filled in the gaps with literary licence.”

Nevertheless, that licence allowed Capote to flesh out the two murderers, Richard Hickock and Perry Smith: Norman Mailer hailed In Cold Blood’s Smith as among the great characters of American literature. Capote allowed readers what felt like unparalleled access into the mind of a killer. “I could always tell when Dick or Perry wasn't telling the truth,” Capote said in a 1966 interview for The New York Times. “I would keep crossing their stories, and what correlated, what checked out identically, was the truth.” He took time developing an intimacy with Smith. “It wasn't until the last five years of his life that he was totally and absolutely honest with me, and came to trust me. I came to have great rapport with him right up through his last day.”

Errol Morris/YouTube

Errol Morris/YouTubeReconstruct the crime

The creators of Making a Murderer are keen to emphasise they weren’t interested in proving whether Avery and Dassey were guilty or not – instead, they claim, they aimed to show the holes in the legal process that convicted them. One landmark true crime story had a more investigative angle: its director, Errol Morris, had worked as a private detective before embarking on The Thin Blue Line.

The 1988 documentary pioneered an approach of re-enacting scenes based on witness statements. Morris later wrote in the New York Times: “We assemble our picture of reality from details. We don’t take in reality whole. Our ideas about reality come from bits and pieces of experience. We try to assemble them into something that has a consistent narrative.” Through small details, he examined the case against the 26-year-old Randall Dale Adams, who had been sentenced to death for the murder of a Dallas police officer in 1976. A spilled milkshake; the occupants of a car with its headlights off.

As a result of Morris’s film, Adams had his conviction overturned and he was freed in 1989. “It wasn’t a cinéma vérité documentary that got Randall Dale Adams out of prison. It was a film that re-enacted important details of the crime. It was an investigation – part of which was done with a camera,” wrote Morris in the New York Times. “Memory is an elastic affair… My re-enactments focus our attention on some specific detail or object that helps us look beyond the surface of images to something hidden, something deeper – something that better captures what really happened.”

HBO

HBOElicit a confession

The day before the finale of The Jinx aired in March 2015, its subject was arrested for first-degree murder: a scene at the end of the six-part HBO series was labelled “one of the most jaw-dropping moments in television history”. Real-estate heir Robert Durst had taken part in more than 20 hours of interviews with film-maker Andrew Jarecki, discussing allegations surrounding the 1982 disappearance of his wife Kathleen as well as the murder of a writer in 2000 and Durst’s neighbour in 2001.

After Jarecki confronted him with a piece of previously unseen evidence, Durst went into a bathroom, unaware his microphone was still on, and whispered “What the hell did I do? Killed them all, of course.” It was the culmination of 10 years in researching Durst.

“These two producers did what law enforcement in three states could not do in 30 years,” said Jeanine Pirro, the former Westchester County district attorney, who investigated Kathleen Durst’s disappearance for six years. “Kudos to them. They were meticulous. They were focused. They were clear.” A former federal prosecutor who is a professor at Columbia University Law School, Daniel Richman, has said Durst’s bathroom comments could be itted in court “so long as it can be shown that the tape wasn’t tampered with”.

Jonathan Hanson/Syed family

Jonathan Hanson/Syed familyLeave it open

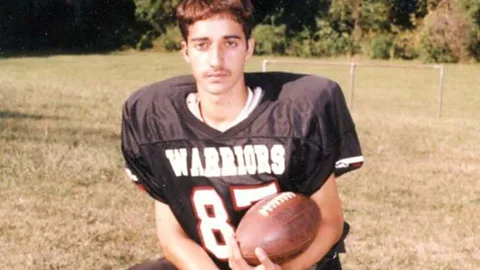

Making a Murderer’s creators have attempted to deter one disturbing trend associated with recent true-crime shows: the rise of the internet private eye. “We always hoped that there would be viewer engagement, we just had no idea that people would become amateur sleuths,” Ricciardi told The Daily Beast. “I guess it’s just the times we’re living in. But in of people zeroing in on particular individuals, we would just ask that people check themselves because part of the problem we saw – not only in the 1985 case, but I would argue as well in the 2005 case – was an incredible rush to judgement.” Trial by social media came to the fore with the first series of the podcast Serial, about the conviction of high-school student Adnan Syed for the 1999 murder of his 18-year-old girlfriend Hae Min Lee.

The 12 episodes involved so many twists and turns, as Serial’s host Sarah Koenig herself professed bafflement over whether Syed was guilty or not, that listeners chose to become detectives themselves. Between its launch in October 2014 and the airing of its final episode two months later, fans launched their own investigations on reddit – leading to fears about breaches of privacy for those mentioned in the podcast.

A month after the last episode aired, a Maryland court agreed to allow Syed’s lawyers to move forward with the appeals process – new evidence had surfaced in part due to Serial’s popularity. Koenig acknowledged that embarking on the series without having a sense of its conclusion was risky, but she told Vulture: “I want people to trust that I know what I’m doing and can bring this home… if I learned anything from my time at This American Life, it’s how to craft a narrative so that even if the ending is ambiguous, it is somehow satisfying.” She was uneasy with not knowing, but steered clear of attempting to wrap things up. “I don't know that I'll ever be at peace with what we find or that there will be a definitive verdict. I'm not going to pick a side just because I'm supposed to for a Hollywood ending. I'll pick a side if the reporting gets me there.”

It’s arguably the ultimate test of a true-crime storyteller, and is one that keeps them from turning research into fiction. “What I learned from making this series is the humility to accept that I don’t know, and I may never know,” said Making a Murderer’s Demos. “That was one of the things we learned doing this: just because you have questions doesn’t mean that you’re going to get an answer,” she said. “If you’re so committed to finding the truth and finding the answer, it’s very hard to be comfortable with ambiguity.”