The many lives of Mr Darcy

PR

PRPride and Prejudice and Zombies is the latest in a long line of Jane Austen spin-offs, but what makes her work so ripe for reinterpretation? Lucy Scholes takes a look.

When it comes to much-loved literary classics, the process of adaptation is fraught enough; but when it comes to spin-offs and re-imaginings the ante is upped significantly. This spring sees the arrival of two anticipated additions to the ever-swelling Pride and Prejudice canon: Burr Steers’s film Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, based on Seth Grahame-Smith’s bestselling literary-horror mash-up of the same title, in which the Bennet girls defend themselves against a bloodthirsty army of the undead; and Eligible, Curtis Sittenfeld’s novel that swaps early 19th Century England for contemporary Cincinnati.

The latter is the fourth offering from The Austen Project – re-writings of each of Austen’s six novels for modern audiences – preceded by Alexander McCall Smith’s Emma, Val McDermid’s Northanger Abbey, and Joanna Trollope’s Sense and Sensibility.

Reinventing the classics is not exactly a new idea. Hogarth, an imprint of Penguin Random House in the UK, have a similar project underway in which acclaimed authors are creating new novels based on Shakespeare’s plays, and sca Segal won a host of prizes for her novel The Innocents, an inspired update of Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence that transported the characters from the high society of 1870s New York to the tight-knit Jewish community of 21st Century Hampstead Garden Suburb. However, there’s something about Pride and Prejudice that has inspired a simply astonishing number of ‘variations’ across the widest breadth of genres imaginable.

Spin-offs such as Elizabeth Adams’s The Houseguest, Lara S Ormiston’s Unequal Affections or Kara Louise’s Only Mr Darcy Will Do lean toward explorations of ‘what if’ scenarios. The conclusion is the same – the supercilious Darcy and headstrong Elizabeth are united in marriage – but their courtship takes a different route to that imagined by Austen. Then there are those versions that explore an alternative perspective, such as Pamela Aidan’s Fitzwilliam Darcy, Gentleman trilogy, which tells the story from Darcy’s point of view, or the forthcoming teen novel Lydia: The Bad Bennet Girl by Natasha Farrant.

While these tend towards the realm of fanfiction, sequels provide more mainstream and critically acclaimed offerings. Think, for example, of Jo Baker’s below stairs portrait of the Bennet household in Longbourn, or PD James’s Death Comes to Pemberley, which sees Darcy and Elizabeth’s marital bliss interrupted by a violent murder.

Spank me, Mr Darcy?

These titles, however, are only the tip of the iceberg. The more I looked, the more I found, some more far-fetched than others, such as the Mr and Mrs Darcy Mysteries series by Carrie Bebris, in which the newlyweds turn amateur detectives, or the paranormal adventures in Karalynne Mackrory’s Haunting Mr Darcy. And, call me naïve, but I had no idea there was such a wealth of Pride and Prejudice erotica out there; though when it comes to titles like Pride and Penetration, I suppose I shouldn’t have been surprised. Many of these – Spank Me, Mr Darcy, for example, or Mr Darcy Vibrates – make it abundantly clear that Austen’s arrogant yet enigmatic bachelor has a rich and vigorous existence in many readers’ fantasy lives.

It would appear that the 1995 BBC TV mini-series adaptation, written by Andrew Davies and starring Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth, has a lot to answer for here. Previously the sexual fantasy of a particular type of bookish romantic – her readers often assumed to match the stereotype of Austen herself, “this English spinster of the middle class,” as WH Auden described her – Davies’s now infamous lake scene turned Firth into a universally acknowledged sex symbol, as well as introducing Darcy’s charms to the wider world.

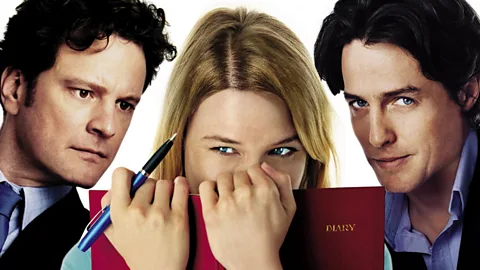

And if Davies’s adaptation can be held able for kick-starting this current era of Pride and Prejudice obsession – not too bold a claim given that every variation (film, TV or book) I came across has appeared since 1995 – then it’s Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary that has the honour of being the first to make the most of this inspiration. Fielding is often quoted as happily itting she “pillaged her plot” from Austen’s novel. The connections between the original, the adaptation and this re-imagining were always clear – Bridget compares Colin Firth’s Darcy with her own Mark Darcy while watching the drama – but things became gloriously complicated when Firth himself was cast as Bridget’s love interest in the 2001 film adaptation of Bridget Jones’s Diary.

Class and country houses

Sequels and reimaginings aside, there’s also clearly something about Pride and Prejudice that makes it ripe for a more nuanced manipulation. Bridget Jones, the TV series Lost in Austen, Austenland, a novel in which a fan finds love in a set-up that mimics the plot of Pride and Prejudice, and The Jane Austen Book Club, a bestselling novel by Karen Joy Fowler, in which parallels are drawn between each of the love lives of the six book group and one of Austen’s novels – all demonstrate the malleability of the original plot.

PR

PR“I’m not sure what exactly are the features that make it easy to transport a story to another time, move the peripheral characters to the front, the protagonists to the back,” Fowler told me. “But there is a lot of room for the reader left in her books. She’s left a lot of space for you to doodle in.”

Of course, we can’t underestimate the enduring appeal of the original text. It’s a novel that presents a version of England that’s often idealised, that of class and grand country houses of the like that, despite being increasingly outdated, appears to exert a nostalgic charm over the popular imagination. You only have to look at the popularity of Downton Abbey to see this at work. This mise en scène alone contains a not insubstantial dose of romance, but add the burgeoning relationship between Darcy and Elizabeth, and you’ve got something close to the perfect love story.

However, despite these picturesque elements, it’s actually a story very much grounded in reality. Elizabeth and Darcy’s happiness is hard earned after a series of humbling and all too human complications and ineptitudes. It’s a novel that “teaches us that no one is perfect,” the literary agent Lucy Luck told me when I asked what makes it still so popular today. “We all know love is irrational,” said the writer Brett Marie. “What Pride and Prejudice shows me is that resistance to love is often based on beliefs that are just as dumb.” It’s a fairytale, but a highly believable one at that. “Lizzy and Darcy seem well matched,” Fowler responded to the same question. “Both have things to learn and learn them. They seem like equal partners.”

The same realism that defines Elizabeth and Darcy’s interactions extend to each and every character in the novel; figures that are “unquestionably one key to her greatness,” argues Robert McCrum in the Guardian. “Her understanding of the human heart is forensic and also frosted with the necessary detachment that gives deeper meaning to her rendering of human frailty,” he continues. “Comic as they are, the clergymen in Austen, like her colonels, widows and spinsters are all rooted in a recognisable and timeless milieu. As she famously noted: ‘Three or four families in a country village is the very thing to work on.’”

Back to the future

Even so, successful re-imaginings are hard to pull off. Austen’s novel Emma has fared rather well here – Amy Heckerling’s 1995 film Clueless did a wonderful job of transposing the original story onto a Beverly Hills high school, while the Daily Beast’s Nicolaus Mills likened the TV show Girls’ Hannah Horvath to Emma Woodhouse. Pride and Prejudice’s marriage plot is perhaps harder to translate to the contemporary.

Gurinder Chadha’s Bollywood version Bride and Prejudice didn’t impress the critics, while Bernie Su and Kate Rorick’s The Secret Diary of Lizzie Bennet struck a slightly false chord given it seemed unlikely that any modern mother would expend the same amount of energy as the original Mrs Bennet in trying to get her twenty-four-year-old daughter married off 19th Century style.

PR

PREligible works particularly well though because it both stays true to the most successful elements of the original text, but has been meticulously updated along the way. Sittenfeld ages Liz and Jane by nearly 20 years, for example, turning them into those most feared of modern day pariahs: the single woman about to turn 40 whose biological clock is ticking!

Chip Bingley isn’t simply “a young man of large fortune,” his reputation precedes him due to his recent appearance on the Bachelor-like TV show Eligible, at the end of which, rather than selecting a bride from the final two candidates, he “wept profusely” and pleaded a lack of “soul connection” with either. And, most perfect of all, Darcy and Liz are having hot “hate sex” long before they can hold a civil conversation.

Of course, when it comes to Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, this sense of continuity couldn’t be further from the truth. If anything, it’s exactly the opposite scenario at work: the appeal is the glaring juxtaposition of the genteel comedy of manners and morals with fantasy-inspired violence and gore. Not that Austen’s own wilful Elizabeth wouldn’t have done her best to hold her own in battle, I’m sure!

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.