Would sex with a robot be infidelity?

HBO

HBOWestworld raises questions about the future of our increasingly digitised sex lives – and more, writes Brandon Ambrosino.

Imagine you’re rich enough to spend $40,000 to visit a town for a day where rules don’t matter. You can be whomever you want. You can kill whomever you want. You can rape whomever you want. You can force every single person you encounter to honour your every sadistic whim. There are no consequences for your actions in this town. Only a few people will find out about your behaviour, and they will encourage you to keep acting this way.

Sounds evil, right?

Now imagine the same scenario, with just one twist: everyone you force into sex is a robot. Everyone you shoot in the head is a robot. The people you torture and manipulate and fondle aren’t actually human. They were created to serve you and to satisfy you and to let you achieve whatever victory you want.

Does that sound as evil as the first scenario?

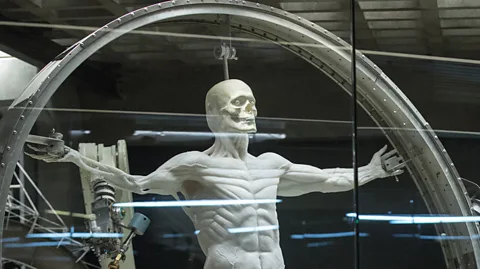

This is one of the major ideas being explored in Westworld, HBO’s newest drama, about a Wild West-themed amusement park where guests are able to do whatever they wish to the ‘hosts’, or robots, who populate the resort. As Bernard (Jeffrey Wright), a programmer, puts it to one of the robots, “you and everyone you know were built to gratify the desires of the people who pay to visit your world.” And importantly, robots can’t ever retaliate and hurt the guests. That’s the idea, anyway… but three episodes into the series it seems like trouble’s well on its way.

HBO

HBO“All kids rebel,” warns head of security Ashley Stubbs (Luke Hemsworth). Indeed, the robots’ father, as it were, Dr Robert Ford (Anthony Hopkins), seems to want them to. In the pilot episode, we learn that Ford has “accidentally” introduced a glitch into the host’s cognition that allows them to occasionally and sporadically the past – certainly horrifying given that their pasts include brutal rape and violent deaths. These rushes of memory seem to be bringing a higher form of self-awareness to the hosts, some of whom are beginning to question the nature of their realities. And while some park stakeholders and designers fear the ramifications of such glitches, Ford seems eager to watch his creations move into their next stage of evolution.

HBO

HBOWestworld forces viewers to confront urgent questions about our future - particularly as they relate to our increasingly wired sense of eroticism. These are questions that many of us have previously dismissed as sci-fi silliness.

Cybersex

“You’re always paying for it, darling,” Maeve Millay, heistress of a brothel, tells Teddy (James Marsden). “The difference is our costs are fixed and placed right there on the door.”

Maeve, played by Thandie Newton, is challenging Teddy to rethink prostitution. She’s suggesting that any woman you make love to will eventually cost you money, but with them there are no hidden costs.

Are there not?

Maeve is a host. She’s engineered to be sexy, and to seduce any guest whom she senses is looking for a good time. That includes partnered guests, like William (Jimmi Simpson), who rejects several robot advances because he has “somebody real” at home.

But what does “real” mean? The robots, right down to their genitals, which we regularly see, look and function exactly like humans’ do. Their sighs and kisses and moans and orgasms seem like the real thing. And yet, says Lee Sizemore (Simon Quarterman), the park’s narrative director, “This place works because the guests know the hosts aren’t real.” It has to be that way, he argues, because no human wants “to imagine her husband is really [having sex with] that beautiful girl.” Which raises a very interesting question: how real does sex have to be to constitute infidelity?

In one sense, the sex that happens in Westworld is digital, if by that we mean it takes place in a computerised version of reality. But at the same time, the sex in Westworld involves bodies that are compatible with each other – even if those bodies are somehow formed differently – so we can conclude the sex is happening with embodied beings in a real time and place.

Kino Lorber

Kino LorberSome critics are outraged that Westworld depicts sexual violence. They focus their rage on the sexual violence perpetrated against Dolores (Evan Rachel Wood), who, like Maeve, is starting to have flashes of her past, which unfortunately contains a lot of sexual violence.

But Dolores and Maeve aren’t the only hosts programmed to gratify the guests. Literally every single robot in Westworld is at the mercy of the visitors’ wills. If that’s the case, then in what sense can we say that any sexual acts in the theme park are consensual? Our concept of permission depends on the possibility of being told no. Even when hosts sleep with other hosts, they’re merely obeying the man who designed their narratives. Beyond the realm of sex, in what sense can we say that any interaction between a host and guest is consensual?

The ‘real’ you

Westworld is a choose-your-own-adventure. Hosts are programmed with more than 100 interconnected narratives, which are set off depending on the specific choices the guests make at any given moment. Some guests choose to ride a horse, others to hunt bandits and others to pummel every host they encounter. Logan (Ben Barnes), a return guest, seems to get off on inflicting terror on the westerners. At one point, he stabs an older gentleman in the hand simply because he can. To him, that’s the point of the park: kill when you want because there are no repercussions.

Logan seems like a psychopath - until we that, well, most of us have been there. As Laura Hudson asks at Vulture, is there any real difference between Logan and “some 15-year-old kid beating a virtual sex worker to death in Grand Theft Auto just because he can?” Sure, it’s probably easier to shoot a 3-inch avatar on a TV screen than a 6-ft humanoid standing right in front of you. But the point is, both killings are defended with the same argument: it’s just a game.

Warner Bros

Warner BrosTrue enough, but there’s a difference in Westworld: the hosts seem to feel pain and fear and terror. “Look at her wriggle!” one guest exclaims while watching the host her husband just shot slowly die on the ground. And as sick as that seems, we need to be consistent with our moral judgments: if sharing an orgasm with a robot doesn’t constitute infidelity, then killing one of them doesn’t constitute murder.

One way the park’s operators might defend the mistreatment of its hosts is by arguing that their traumas are erased from their memories every night. But that argument is based on the premise that the only reason it’s wrong to inflict pain on another being is because they will it. This is obviously not the case. Further, this seems to be a moot point because the fact is the hosts are slowly ing the traumas they’ve experienced. And some of the designers know it - which signals that the masterminds behind the experiment aren’t terribly concerned with ethics.

ABC

ABCNo doubt Westworld will continue exploring questions most of us haven’t yet thought of. But we shouldn’t pretend these questions only belong to the domains of technologists and futurists. As social psychologist Sherry Turkle, who investigates our relationship with technology, has pointed out, our conversations about the future shouldn’t obsess over what robots will be like. Instead, she says, we should think what kind of people we will be, what kind of people we are becoming, every day, whether we’re watching porn, making love to our partners, trying to outsmart Siri or killing an avatar for no other reason than that’s what happens in a video game.

Ford claims to understand why humans are willing to pay so much money to kill and have sex with robots. killings are defended with the same argument: it’s just a game.“They’re here because they want a glimpse of who they could be.”

Logan understands this intuitively. By the end of this trip, he tells William as the two ride into the park, “you’re gonna be begging me to stay, because this place is the answer to that question you've been asking yourself: who you really are. And I can't wait to meet that guy."

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.