Another kind of life: Fascinating photos of outsiders

Mary Ellen Mark

Mary Ellen MarkA new exhibition explores the fringes of society, with photos of US street kids, Tokyo gangsters and Soviet hippies.

“I’m interested in people who aren’t the lucky ones, who maybe have a tougher time surviving, and telling their story.” This quote from Mary Ellen Mark, one of 20 photographers featured in a new exhibition at the Barbican in London, reveals a common thread in the show. While the images range from New York street kids to tattooed Tokyo yakuza, and motorbike gangs to circus performers, they are all the result of a partnership between photographer and subject.

Another Kind of Life: Photography on the Margins includes more than 300 works from the 1950s to today. “These are all photographers who in some way have a sustained and meaningful engagement with the communities and individuals they’re photographing,” curator Alona Pardo tells BBC Culture. “Whether it’s Paz Errázuriz, who lived in brothels with transgender communities… or Teresa Margolles who spent 10 years working with transgender sex workers.”

Walter Pfeiffer

Walter PfeifferWhile the images document people who live on the edges, outside of the mainstream, there is never a sense of voyeurism, or exploitation. “For some of the artists and bodies of work we’re showing, it’s about their own personal participation in those worlds,” says Pardo. “Others have managed to get through the door, they were outsiders but they become insiders, at least for a certain amount of time in order for their subjects to begin to trust them and to feel comfortable. But whether it’s temporarily or permanently, they all begin to live as one with these communities.”

Positive exposure

Errázuriz sees her work as anthropological. “There’s this relationship that she enters into with the community and the subjects where she tries to understand and share the experience with them – and then the viewer,” says Pardo. The Chilean photographer was a school teacher when Augusto Pinochet seized power in 1973 after a military coup. She gave up teaching, and picked up her camera.

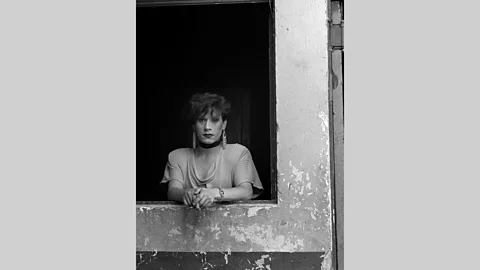

Paz Errázuriz

Paz Errázuriz“Photography let me participate in my own way in the resistance,” Errázuriz has said. “It was our means of showing that we were there and fighting back.” She chose to photograph those targeted by the new regime. After befriending a group of male cross-dressers, some of whom worked as prostitutes, she lived with them in clandestine brothels across the cities of Santiago and Talca. Errázuriz worked on her Adam’s Apple series for almost a decade, developing a close relationship with two transvestite brothers, Pilar and Evelyn.

Paz Errázuriz

Paz Errázuriz“I do not comment on their lives, I wanted to be more of an accomplice than a foreigner or outsider,” she has said. And while her images aren’t overtly political, her work was an act of defiance. “The community that she was photographing were subjects of persecution, police brutality,” says Pardo. “Not only were the figures she was photographing living a very furtive experience under the radar of this highly regulated and controlling regime – away from their gaze – but as a photographer as well, she experienced great personal risk. So it becomes not only an act of political resistance for her but the photography also captures that and stands very defiantly against the regime.”

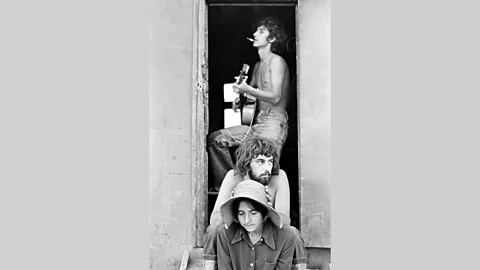

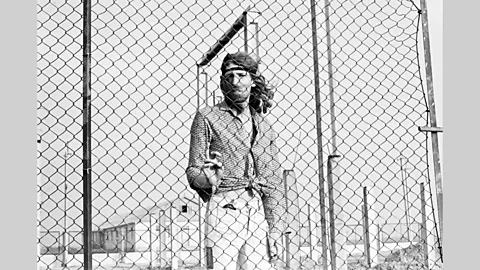

Another photographer whose work challenged the establishment in a subtle way, Igor Palmin, captured images of hippies in the Soviet Union that are far removed from ‘Summer of Love’ clichés. Described in the Another Kind of Life catalogue as “photos of forlorn countercultural youths populating an apocalyptic post-industrial landscape”, the images were taken at the site of an archaeological dig in 1977.

“These figures were the children of a fairly privileged background, because they could afford potentially not to work,” says Pardo. “They’d go on these archaeological digs and become labourers on these digs to help the academics and archaeologists in their toils, but they don’t really do very much and they wore bell bottoms and hairbands and had long wavy hair and they ditched all their own clothes, and listened to the Russian equivalent of alternative music.”

Igor Palmin

Igor PalminThey occupied an ambiguous place in Soviet culture. “It was a deeply anti-Soviet position that they took, although they themselves would say that they were apolitical,” says Pardo. While the hippy movement was spread through music or fashion or style – initially by the children of diplomats, exposed to Western ideas – it signalled a form of defiance. “It becomes very political, and it was to a degree ed by the Soviet regime, because it was seen as anti-capitalist – but ultimately it was anti-authoritarian, it’s anti-establishment,” says Pardo. “Work was a very important thing within the Socialist economy, you had to live within that system, so it’s circumnavigating that system.”

Born to be free

Palmin’s photos focus on one man, who is seen drifting through warehouses or standing on rusting industrial machinery – the series is called The Enchanted Wanderer. “It has Bob Dylanesque moments, utopian moments, but it becomes political here – the enchanted wanderer didn’t have to go through military service because he said that he had a psychiatric issue,” says Pardo. “They learnt to work the system in their favour to avoid living what was deemed the ‘Soviet lifestyle’ – which was to work, to get a job, to get married.

Igor Palmin

Igor Palmin“They’re constantly fighting against that – and they have to do that through various means, whether it’s by g yourself off in psychiatric as mentally ill, or making ends meet by working on archaeological digs – because these were the places that were slightly out of the gaze of the controlling authorities, where they could be a bit more free – and that comes across.”

Some of the photos in Another Kind of Life reveal groups who could only find their freedom in hidden ways. The Casa Susanna series features portraits of male cross-dressers taken at a resort in New York during the 50s and 60s. Perched on a footstool in negligee and high heels, leaning on a mantelpiece in a twinset and pencil skirt, sitting on a swing in a summer dress – the subjects look proudly at the camera or angle their heads with a coy smile, posing in a place without judgement.

Art Gallery of Ontario

Art Gallery of OntarioThe photos were discovered at a flea market in 2004, many carefully arranged in albums. “The act of posing for a photograph allowed… a chance to bring that woman to life in a way that only photographs can,” writes Sophie Hackett in the exhibition catalogue. “It is both playful play and serious play, a visual journey to discover through these photographs: which self suits best?”

The cross-dressers of Casa Susanna were involved in political change as well as personal transformation. “The magazine that was established as a result of that retreat, Transvestia, called for not only public acceptance of the burgeoning transgender community, but also legal protection and general awareness,” says Pardo. “I use the word acceptance, but I also want to use the word appreciation – this idea that we wanted to appreciate, and reinstate, these other communities that form part of our society.”

That’s true for all the images in Another Kind of Life. “It’s key to think that these bodies of work that gave representation to these communities, and were then published and seen and critically acclaimed, have helped us to understand better the plurality of voices in our world,” says Pardo. “It has given them a visual record which is critical – we’re a very visual animal, human beings – and by giving that a visual record, that has to have had an impact. If you look at any magazine today, you can see their legacy of these photographers, not only in their aesthetic attitudes but also in the subject matter, and what they chose to focus their camera on.”

Teresa Margolles

Teresa MargollesAnd many of the issues captured in photos from half a century ago can still inform us now. “It’s interesting to think about the Casa Susanna material, because that was happening in the 50s, but if you look at Teresa Margolles’s photographs of transgender sex workers on the US-Mexican border taken in 2016 – not much has changed. They’re still subject to brutality, discrimination of all sorts.”

Photography, argues Pardo, is one of the best ways to challenge that. “These are the forgotten and the marginalised – those that we wish not to see – and the photos are very much about giving them representation – they’ve shed all kinds of judgement, there isn’t judgement, there is just a desire to reflect accurately and as authentically as possible the daily grind that some communities have to go through.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.