The mysterious, macabre mind of Edward Gorey

Brennan Cavanaugh

Brennan CavanaughA new biography looks at the appeal of Edward Gorey. Why have so many directors and writers been drawn to his peculiar vision, asks Cath Pound.

From the Gashlycrumb Tinies to The Doubtful Guest, Edward Gorey’s morbidly funny little books are gothic surrealist masterpieces. Drawing on sources as varied as the novels of Agatha Christie and French silent film, he created a uniquely macabre vision of the world filled with crumbling English mansions, jittery dark-eyed flappers and stony faced Edwardian gents where nothing is quite as it seems. His virtuosic illustrations and poetic texts have drawn comparisons to Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear and Samuel Beckett, winning him critical acclaim and a devoted cult following in his native US.

More like this:

- Alice in Wonderland’s hidden messages

That he is not better known elsewhere is perhaps due to the unclassifiable nature of his work – yet his influence can be seen everywhere, from the films of Tim Burton to the novels of Neil Gaiman and Lemony Snicket.

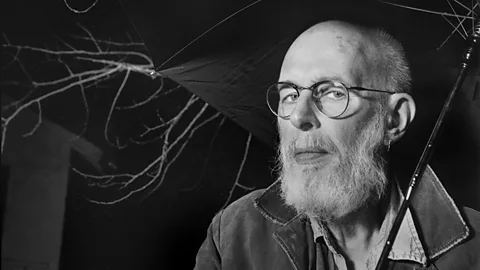

Gorey himself was a complicated, reclusive individual whose mission in life was “to make everybody as uneasy as possible”. He collected daguerreotypes of dead babies and lived alone with 20,000 books and six cats in his New York apartment. Sporting an Edwardian beard, he would frequently traipse around the city in a full-length fur coat accessorised with trainers and jangling bracelets.

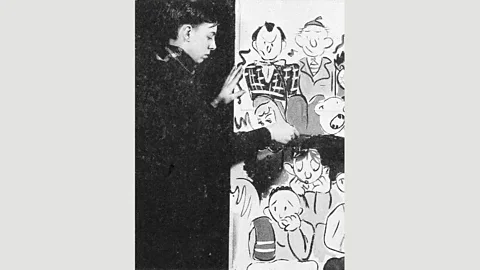

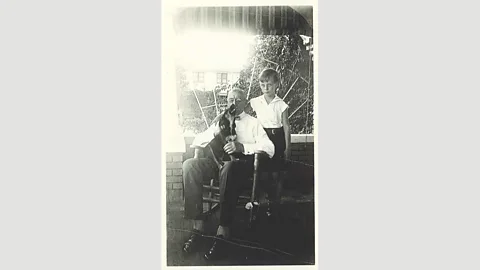

Francis W Parker School, Chicago

Francis W Parker School, ChicagoA precociously gifted child, he grew up in depression-era Chicago, learning to draw at the age of one-and-a-half and teaching himself to read at three. He had devoured Dracula by the age of five and the complete works of Victor Hugo before he was eight, absorbing a gothic sensibility which would later imprint itself on his work.

A mystery wrapped in an enigma

The country house murder mysteries of favourites such as Christie and Dorothy L Sayers nurtured his Anglophilia – although he never actually visited England. Friends believe his fantasy could never have coped with the reality. Regular trips to the theatre, ballet and concerts were instrumental in turning him into a cultural omnivore, a tendency which expanded even further once he entered Harvard after World War Two.

Here his social circle revolved around what Mark Dery, author of Gorey’s first major biography Born to be Posthumous, refers to as the “gay literati”, including the poet Frank O’Hara with whom he shared a ion for obscure literature. Although most people who met him assumed Gorey was also gay, he was notoriously reticent on the subject. When one interviewer pressed him on his sex life, “he responded: ‘I’m a person first, an artist a distant second and whatever else last,’” says Dery.

There is certainly an undercurrent of homoeroticism, gender fluidity and same-sex couplings running throughout Gorey’s oeuvre and he noted in a letter to a friend that ‘les boys’, as he phrased it, appeared to be among the first to appreciate his unusual works.

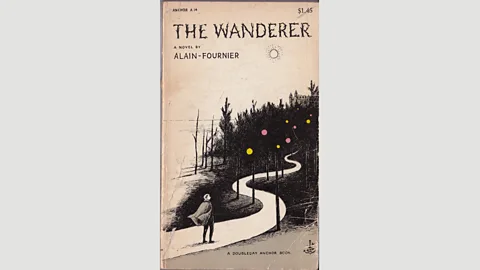

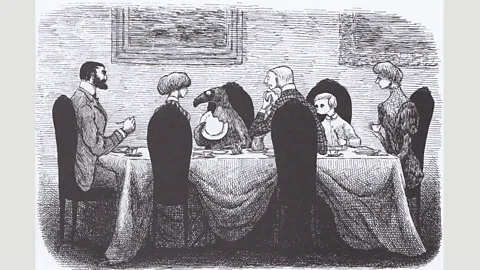

Doubleday Anchor Books, 1953

Doubleday Anchor Books, 1953Gorey’s unique style first came to public notice as a designer of paperback covers for Doubleday’s Anchor Books imprint. His elegantly elongated figures and sombre palette, inspired both by the English illustrator Edward Ardizzone and the Japanese Ukiyo-e prints he loved, were in marked contrast to the pulp fiction-inspired covers prevalent at the time.

The Anchor job meant a move to New York, which did not enthuse him, but opened up a whole new world of cultural possibilities. At the silent film evenings run by the film historian William K Everson, he discovered the work of French film-maker Louis Feuillade. His gothic-macabre crime thrillers Fantômas and Les Vampires would become “the greatest influence on my work. Period,” Gorey later said. The potted palms, pattern-on-pattern decor in interior sets and mysteriously veiled women in dark clothes who populated his films would become instantly recognisable Gorey motifs.

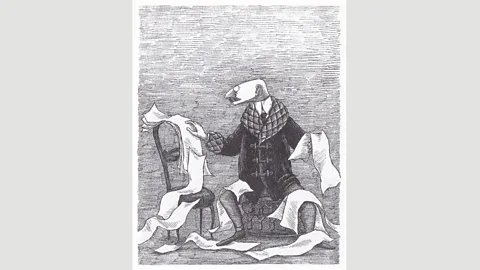

Duell, Sloan and Pearce/Little, Brown

Duell, Sloan and Pearce/Little, BrownGorey’s first venture into publishing his own work was The Unstrung Harp, originally published in 1953. Set in what was to become his familiar Victorian-Edwardian nether world, it tells the tale of Mr Earbrass’s tortured attempts to write a novel.

However, the book’s smaller format was as difficult to place as its genre – neither a children’s book nor humour – leading to indifference from booksellers and poor sales.

Doubleday, 1957

Doubleday, 1957Undeterred, he continued in the same vein, hitting an early high with his third book, The Doubtful Guest (1957), a gothic-Surrealist tale dedicated to his friend Alison Lurie. As she had recently become a mother, many see the book’s penguin-like protagonist as a caricature of infancy, but with its canvas shoes and Harvard scarf it is difficult not to also see the strange outsider as a poetic evocation of Gorey as a child.

Elizabeth Morton, private collection

Elizabeth Morton, private collectionAs ever, when it came to meaning, Gorey was tight lipped. “He wants to leave these lacunae, these gaps, that entice the reader to collaborate with him and generate his or her own meanings and for that reason, his work is endlessly rich,” says Dery.

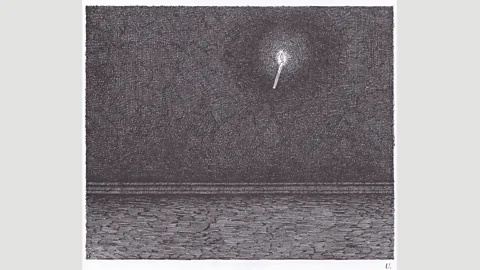

Simon and Schuster

Simon and SchusterPerhaps his finest example of poetic ambiguity can be found in The West Wing (1963). Entirely wordless, it features a series of seemingly unrelated s depicting eerily unsettling rooms which, we gradually come to realise, are in all likelihood set in the after-world.

Reluctantly famous

He would eventually produce more than 100 of these miniature masterpieces, many in extremely limited editions. The Gashlycrumb Tinies (1963), his gruesomely hilarious alphabet book in which a series of children meet ghastly ends, is probably the best known.

Despite an almost pathological loathing for self-promotion, fame finally caught up with Gorey in the 1970s. Andreas Brown, proprietor of the legendary New York book store The Gotham Bookmart and a long-time er of Gorey, persuaded him to release an anthology of his hard-to-find early titles. The resulting Amphigorey (1972), produced in a format which actually suited conventional bookstores, became an instant best-seller.

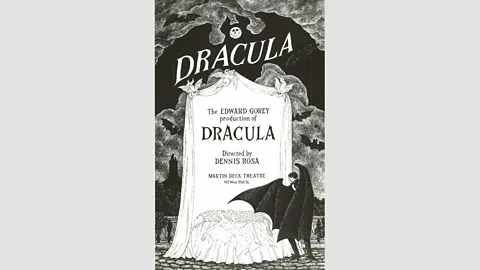

The Edward Gorey Charitable Trust

The Edward Gorey Charitable TrustBut it was his Tony Award-winning designs for the Broadway production of Dracula that truly turned him into a star, even leading to a range of fur coats and Gorey-inspired wallpapers. When he was then asked to design the titles for the PBS series Mystery, his work became known to millions throughout the US. However, as Gregory Hischak, curator of The Edward Gorey House, notes, “he didn’t like having himself displayed like that. He was a very private person.”

In 1983, he quit New York for Cape Cod, hanging up his fur coats and buying a suitably ramshackle house with the money he’d made from Dracula. “He converted back to what he liked doing, which was drawing, and kept a lower public profile,” says Hischak.

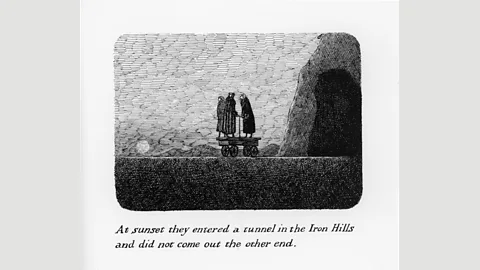

Bobbs-Merrill, 1962

Bobbs-Merrill, 1962But his unique aesthetic soon found its way into the work of other similarly macabre-minded creatives. Dery sees his influence in Tim Burton’s work, particularly The Nightmare Before Christmas. The film’s set designer has apparently confirmed that Gorey was a source of inspiration for Halloweentown’s designs, although Burton himself has remained tight-lipped on the subject. Director Guillermo Del Toro is more forthcoming in his iration, calling Crimson Peak his “blood stained valentine” to Gorey.

In literature, Daniel Handler (better known as Lemony Snicket) has openly declared his debt to Gorey, making use of what Dery calls the “tongue-in-cheek aloof ironic quality” of Gorey’s writing in his Series of Unfortunate Events.

Doubleday, 1958

Doubleday, 1958Neil Gaiman is another fan; his macabre novel Coraline bears Gorey’s unmistakable mark. If only Gorey had lived to illustrate it, as Gaiman hoped, he might have found a greater audience in the country that had given him such inspiration. Perhaps Dery’s book will succeed where Gaiman’s couldn’t, and bring a smile to Gorey’s face in whatever room of The West Wing he now inhabits.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.