The films that defined Generation X

Alamy

AlamyTwenty-five years after the release of Reality Bites, Clare Thorp looks at the movies that capture the spirit of a pre-millennial generation.

Twenty-five years ago, when the idea of a millennial was still a twinkle in marketers’ eyes, a film was released in cinemas that set out to capture the spirit of a different generation – one to whom a Discman was cutting-edge technology and avocado was a colour in which your grandmother’s bathroom was painted. Reality Bites was not a huge commercial success in 1994 but, a quarter of a century on, it’s emerged as an iconic portrait of Generation X – the so-called 'forgotten generation'.

In recent years, Gen X (defined as those born between the mid-1960s and the early 1980s) has been edged out of the cultural conversation as the media obsess over millennials and companies court wealthy baby boomers. But for a few years in the late 80s and early 90s, cinema was enthralled with this new breed of teens and twenty-somethings – and many of the films made by and about them have become cult favourites, from teen classics like The Breakfast Club to iconic indies like Before Sunrise.

Alamy

AlamyThe label Generation X emerged in 1991 with the release of Douglas Coupland’s novel, Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. The twenty-somethings in his book were characterised as overeducated, underemployed, cynical and disaffected – a ‘lost generation’ living in the shadow of their baby boomer parents, and rebelling against them.

Though they didn’t have an official title until the early 90s, many had already come of age, and cinema was attempting to capture the mood of this new cohort. In 1985’s The Breakfast Club, John Hughes – himself a boomer – gathered a disparate gang of teenagers together in school detention. They might be “a brain, an athlete, a basket case, a princess, and a criminal” but they had one thing in common – issues with their parents, and a deep desire not to end up like them.

Alamy

AlamyThree years later came black comedy Heathers, which turned high school rivalries into a literal blood sport and starred new Gen X poster girl Winona Ryder as disaffected teenager Veronica. “I guess I picked the wrong time to be a human being,” she sighs to her mother.

Alamy

AlamyIt’s a rare appearance by a parent, largely absent from Gen X films. This was the latchkey generation, where rising divorce rates and an increase in both parents working meant many young people were left to try and figure life out for themselves.

In 1990, Time magazine published a cover story headlined ‘Twentysomething’ examining the post-boomer generation and asking if they were “laid back, late blooming or just lost?” That same year, Richard Linklater premiered his $23,000 (£15,000) film Slacker, which turned the so-called aimlessness of Gen X into an art form. Chronicling a day in the life of young people on the fringes in Austin, Texas, the camera floats from one character to the next, never lingering on one for long.

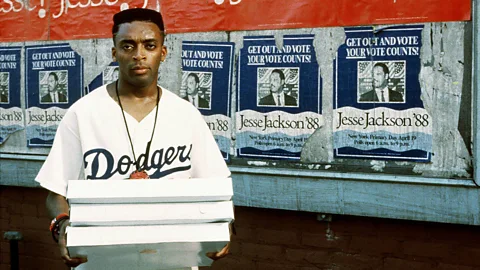

The film became a sleeper hit, eventually taking more than £1million ($1.6million) at the UK box office. Linklater has always refuted that slacker meant lazy. “Being a slacker was a very productive period in my life, though it did not look that way to anyone else,” he said. It was true. By 1995 he had released another two Generation X classics, Dazed and Confused and Before Sunrise. Both were set over 24 hours, a common formula not only for him but many Gen X directors trying to capture a snapshot of a generation. Empire Records (1995) chronicles a day in the life of a group of record store employees, while Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing (1989) is confined to a Brooklyn neighbourhood on a sweltering hot summer’s day. It was also true of Clerks (1994) – Kevin Smith’s directorial debut, a film inspired by Slacker that was made on a budget of $28,000 (£19,000) and follows a day in the lives of two convenience store workers.

Alamy

AlamyTime was something this generation seemed to have a lot of. “There’s this idea that their parents’ generation, the boomers, had all these great causes that they were fighting for – civil rights, women’s rights, gay liberation,” says James Lyons, a lecturer in film at the University of Exeter. “Gen X didn’t have those causes to rally round in the same way and, without those issues, they didn’t quite know what to do or where to direct themselves.”

A family affair

The emergence of friends as a new form of family, before Friends itself put the idea in the mainstream, was also a common theme. Cameron Crowe’s Singles, a romantic comedy about twenty-somethings living in the same Seattle apartment block, is one of the films most commonly associated with Generation X. Crowe – himself a baby boomer – describes it as “a story of disconnected single people making their way, forming their own unspoken family” yet insists he never set out to define a generation. But with a soundtrack featuring Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Mudhoney and The Smashing Pumpkins, its 1992 release coincided perfectly with the moment grunge hit the mainstream and Seattle became the most talked about city in the US.

Alamy

AlamyIf Singles accidentally captured a zeitgeist, other films knew exactly what they were doing. Writer Helen Childress was just 20 when a producer read a script she’d written in college and signed her up to write a movie about the lives of a group of twenty-somethings. With the working title “Untitled Baby Busters Project” – referencing an earlier term for the Gen Xers – that script went on to become Reality Bites, a major studio’s attempt to ape indies like Slacker and chronicle the twenty-something generation.

“Reality Bites is aware of the idea of Generation X in a very obvious sort of way,” says Lyons. “It’s very much Hollywood’s attempt to tap into that generation’s sensibility.” Graduates stuck in dead end jobs? Check! Plaid shirts and cool soundtrack? Check! Divorced parents who don’t understand your struggle? Check! It may have been Gen X-by-numbers, but Childress drew on her own experiences for the film to make it feel authentic, using real conversations and even real names.

Alamy

AlamyBy this point, with an early 1990s economic downturn in the US, Coupland’s portrayal of Gen X as overeducated and underemployed was becoming increasingly real. In the film – directed by Ben Stiller – Winona Ryder’s character Lelaina is making a documentary of her friends’ post-graduation lives, which mainly involve retail jobs, failed relationships and empty bank s. Ethan Hawke’s character Troy is an avatar for the cynicism frequently associated with Gen X. When Lelaina says she wants to make a difference in people’s lives, Troy snarks that he’d “like to buy them all a Coke”. Reality Bites also reflected another specific Gen X concern: selling out. At her graduation speech, Lelaina scolds her parents’ generation for swapping their 60s ideals for “a pair of running shoes”.

But if you take away the plaid and the 90s soundtrack, are these films any different to other coming-of-age stories in which young people feel misunderstood? Lyons thinks so. “There’s something about the cynicism and the irony of Generation X that was quite pronounced. The next generation of independent films don’t have that same archness and there’s more of a sincerity about them.”

No filter

There was one Gen X film, though, which was determined to show youth culture at its most raw – without any irony. Larry Clark’s Kids, written by a 19-year-old Harmony Korine, followed the lives of several teenagers over one day in Manhattan, taking in sex, drugs, rape, the spread of HIV and gang violence. The low-budget film had the feel of a documentary, with many of its cast taken straight from the streets of New York, and saw Chloe Sevigny and Rosario Dawson make their film debuts. On release the New Yorker called it “nihilistic pornography”.

Alamy

AlamyKorine has said he doesn’t think Kids would get made today. If it did, it would be a different film in the digital age. Sevigny’s character spends the movie traipsing across New York to warn a former sexual partner she has HIV. Today, she could message him in seconds.

Re-watching these films today, they’re notable as much for what they don’t contain as what they do. You might spot the odd pager or brick-like car phone, but there is no internet, social media or smartphones. Some of the premises would be redundant now. In Before Sunrise, Jessie and Celine would follow each other on Instagram instead of arranging to meet in the same spot in a year’s time. In Reality Bites, Leilana needn’t have worried about a TV company sabotaging her documentary. She could have just stuck it on YouTube.

Yet despite how different millennials’ lives may be, Lyons says they can still connect. “I teach a number of these films and movies like Slacker and Reality Bites do chime with millennial students, particularly that idea of prolonged adolescence.”

Today’s woke generation might struggle with some elements, though. In Reality Bites, Troy is painted as a romantic artist whose bad behaviour is part of his charm – now his constant put-downs and gaslighting would have him quickly pinned as toxic.

Alamy

Alamy“Some of the attitudes in these films absolutely haven’t aged well, particularly gender relations and social politics,” says Lyons. “The representation of Gen X also skewed very white and heavily overrepresented white college-educated twenty-somethings. African-American directors like John Singleton or the Hughes Brothers get sidelined, as does the New Queer Cinema of the early 90s.”

By the time the 90s drew to a close, Generation X was starting to be reexamined. Time, the magazine that had once painted them as “lost”, devoted another cover feature to them. “Slackers? Hardly.” it wrote. “The so-called Generation X turns out to be full of go-getters.” They may have been a bunch of cynics, but Generation X turned out to be more entrepreneurial and creative than any of the films about them predicted – even if no one wants to talk about them now.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.