The TV show that transformed Hinduism

Ramanand Sagar Productions

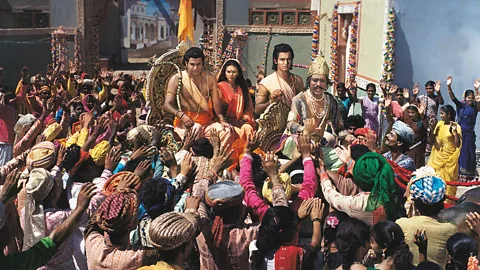

Ramanand Sagar ProductionsDuring 1987 and 1988, Indian state TV broadcast a series that adapted the epic Hindu poem the Ramayana for a modern audience. Some believe this set the path for a national Hindu consciousness, writes Rahul Verma.

As a teenager growing up in late-1980s London, visits to New Delhi to see my extended family were like stepping into another world. On those trips, I’d swap Batman comics for Amar Chitra Katha comic books, depicting wondrous Hindu mythology; cans of cherry coke for glass bottles of Campa Cola; and four terrestrial TV channels for one, Doordarshan.

Whereas in London I had to pester my parents to watch Neighbours and EastEnders, in Delhi they insisted I them, my grandparents, aunt, uncle and cousins to watch the Ramayan. Ramanand Sagar’s TV adaptation of the epic Hindu poem the Ramayana tells the story of crown prince, Lord Ram, who is banished into exile for 14 years, and must rescue his kidnapped wife Sita from the clutches of a ten-headed demon.

More like this:

The victory of light over dark and Lord Ram’s return home to the kingdom of Ayodhya is the basis of Diwali, the festival of light celebrated by Hindus, Sikhs and Jains, that also marks New Year for some communities. In the run-up to Diwali (this year on 27 October), Ramlilas – folk plays of the Ramayana – are performed in schools, halls, markets, and on street corners, in cities, towns and villages, just as the nativity is celebrated before Christmas among Christian communities.

Ramanand Sagar Productions

Ramanand Sagar ProductionsOver the course of 18 months in 1987 and 1988, Sagar’s telling of the epic through 78 weekly 45-minute episodes – broadcast on Sunday mornings on India’s only TV channel, Doordarshan – became the most successful TV show in Indian history, with popular episodes watched by a staggering 80 million to 100 million people, an eighth of the population.

The Ramayana’s special place in India’s cultural memory explains why the TV series became a phenomenon, but no one could have predicted that the Ramayan would become a participatory, weekly act of devotion. As Arvind Rajagopal, professor of media studies at NYU and author of the book Politics After Television, explains, in cities across northern India public life ground to a halt. “Trains would stop at stations, buses would stop, and engers would disembark to find a roadside place with a TV – the crowds were so big, people would be unable to see or hear the TV but the point was about being present, being there.”

Screen worship

The BBC’s Delhi correspondent Soutik Biswas wrote in 2011: “I the soap nearly shutting down India on Sunday mornings in the mid-1980s – streets would be deserted, shops would be closed and people would bathe, and garland their TV sets before the serial began.”

Sunday mornings were the highlight of my grandmother’s week: before the broadcast, she would burn incense and perform pooja (prayer ritual) in the home shrine, before sitting on the floor, barefoot and covering her head with a chunni, to watch the show, along with three generations of family.

My grandmother’s rituals mirrored temple conventions and the series brought the temple experience of darshan – visual communion – into homes and public spaces where it was screened. While in a Hindu temple setting, darshan is about worshippers gazing at statues of gods, with the Ramayan, Hindus were able to visually commune with Hindu gods (Ram, Laxman, Sita, Hanuman) via the TV. “It was absolutely like going to the temple – people would do pooja before the show, put garlands and tikka (red marks) on the TV; that was the kind of feeling people had for the show,” explains the actor Arun Govil, who played Lord Ram.

Ramanand Sagar Productions

Ramanand Sagar ProductionsThe show changed Govil’s life. “Wherever I went people wanted to touch my feet and touch me, there was so much adulation and iration, people would start crying out of happiness. I have a newspaper clipping of when I visited Varanasi in my costume: the headline says ‘One Million People Gather to Look At Lord Ram’,” he recalls.

‘Ramayan Fever’ gripped the nation. On Sunday, August 7, 1988, one week after the series finished, journalist Shailaja Bajpai wrote in the Indian Express (p16): “Never before, and maybe never again, will there be another quite like it. From Kanyakumari to Kashmir, from Gujarat to Gorakhpur, millions have stood, sat and kneeled to watch it. Millions more have fought, shoved and keeled over, watching it.”

The TV show is credited as the catalyst in sparking a Hindu awakening across India, and bringing Hindu nationalism to the forefront of public and political spheres. Until the Ramayan was broadcast, religious TV programming was limited because India is a secular state, with all religions treated equally, as Rajagopal explains. “The broadcast of the Ramayana was the first major rupture of the secular consensus, it catered to the devout and ritualistic. The popular response was devotional, but the activity of political parties was necessary to translate that into something political.”

Ramanand Sagar Productions

Ramanand Sagar ProductionsIn a 2000 interview with India’s Frontline magazine, Rajagopal said that when the Indian government began broadcasting the Ramayan to nationwide audiences, “This violated a decades-old taboo on religious partisanship, and Hindu nationalists made the most of the opportunity. What resulted was perhaps the largest campaign in post-Independence times, irrevocably changing the complexion of Indian politics. The telecast of a religious epic to popular acclaim created the sense of a nation coming together, seeming to confirm the idea of Hindu awakening.”

While it was the Congress government of the time that sought to capture Hindu votes by broadcasting the Ramayan on state TV channel Doordarshan, it is the Hindu nationalist party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), that has reaped the benefits. The BJP, currently led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, convincingly won general elections in India in 2014 and 2019, and led coalition governments from 1998 to 2004.

Holy land

During and after the Ramayan’s broadcast, the Sangh Parivar (family of Hindu nationalist organisations), spotted the chance to capitalise on a Hindu awakening and construct a national Hindu consciousness, as well as unifying diverse Hindu groups and establishing the idea of a golden era of Hindu rule – ‘Ram Rajya’ or Kingdom of Ram. During the series’ transmission there was a controversy over a mosque, the Babri Masjid, in the city of Ayodhya – with Hindu nationalists claiming it was built on the site of Lord Ram’s birthplace.

Ramanand Sagar Productions

Ramanand Sagar ProductionsHindu nationalists orchestrated a nationwide campaign, the Ram Janmabhoomi (meaning ‘Rama’s birthplace’) movement – dressing volunteers as Ram and Laxman from the TV series – calling on the construction of a Lord Ram temple in place of the mosque. Campaigns, including ‘Send a brick to Ayodhya’ and ‘Send a rupee’, enabled Hindus all over India – rich and poor – to contribute to the building of a Hindu temple, and forged a sense of Hindu togetherness.

According to Rajagopal, the Ramayan TV series echoed this movement. “In one scene, Lord Ram reveals he’s carrying earth from his birthplace – this is not in any version of the Ramayana I’m aware of – and spoke to a specific political moment, the Ram Janmabhoomi movement. It’s an example of how the series reflected politics, and vice versa.”

In December 1992, a rally organised by Hindu groups drew 150,000 people – some dressed as characters from the TV show – to march on the 16th-Century mosque in Ayodhya, to march on the 16th-Century mosque in Ayodhya, and violence erupted with mobs tearing down the mosque. Communal violence flared across the country, and the issue remains live, with India’s Supreme Court expected to hand down a ruling in the coming weeks on whether a mosque or temple, or both, should stand on the site.

Ramanand Sagar Productions

Ramanand Sagar ProductionsToday, metaphors and symbols from the TV series and epic are regular features of Indian politics – for example, the concept of the ‘Ram Rajya’ (‘a just and mighty Hindu kingdom’) is ever present, and Prime Minister Modi and BJP president Amit Shah are often referred to as Lord Ram and his brother Laxman. While the TV series is not responsible for this, it made a standard set of Hindu symbols available to all, and these state-sponsored symbols helped create the conditions for a Hindu redefinition of public and political life.

“For Hindu nationalists, the long-held desire has been to establish a devout Hindu character, and through rebuilding the character of the individual you rebuild the character of the nation,” says Rajagopal. “For decades it was believed that this would have to happen on the ground, from the bottom up; however with the opening up of the media landscape and TV they could do it symbolically, top-down rather than bottom-up.”

Modern mythology

A 2018 article in The Hindustan Times reassessing the impact of the TV series argued that “Sagar’s Ramayana played in the backdrop of a Hindutva [Hindu nationalist] shift in Indian politics, under the aegis of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and its political outfit, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). While the media and cultural commentators struggled to consider Sagar’s epic one way or the other, there were some who saw it as a catalyst, even if unintended, to the turmoil that the movement resulted in.”

Ramanand Sagar Productions

Ramanand Sagar ProductionsAnd in many ways, the show’s influence extended beyond symbolism. According to the Hindustan Times article, “The political clout that the TV series came to hold can be adjudged by the fact that Arun Govil (who played Ram) and Sagar were repeatedly courted by both the Congress and the BJP to campaign for them. Other actors like Deepika Chikalia (Sita) and Arvind Trivedi (Ravana) both eventually became MPs.”

What its makers claimed to be the ‘world’s most viewed mythological series’ helped to break TV as a mass phenomenon in India. It also showed that ancient Hinduism was compatible with modernity, ready for a new technological and consumer age, with India on the cusp of major market reform and economic liberalisation in the early 1990s.

More than 30 years after the series ended, the Ramayan is still shaping the actor who starred as Lord Ram. “As an actor, the success wasn’t good for me as I was unable to get different roles. I was told, ‘Your image is so strong as Ram-ji.’ In the beginning that bothered me, but it depends on how you take it. I’m still ed, loved and respected for that role,” says Govil, who is currently starring as Lord Ram in a stage show, The Legend of Ram. And, just as Govil continues to be defined by the Ramayan, so too is India.

Love TV? BBC Culture’s TV fans on Facebook, a community for television fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.