The snowy countries losing their identity

BBC/Javier Hirschfeld/Getty Images

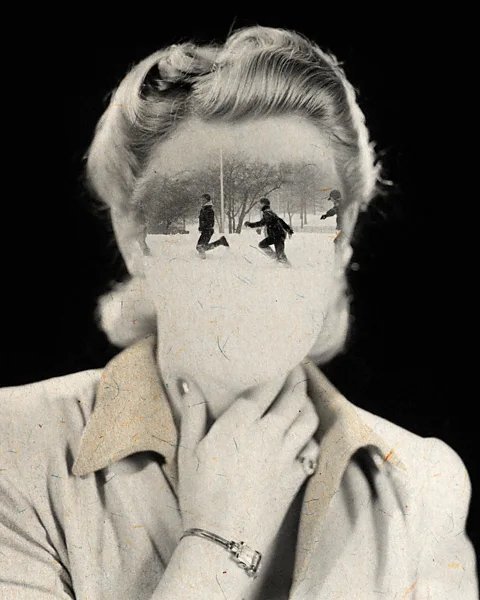

BBC/Javier Hirschfeld/Getty ImagesFor those who grew up marvelling at snowflakes or hurtling downhill on a sledge, how do you adapt to a world where these joys are growing rarer?

A few weeks ago, I woke up to a familiar brightness in my bedroom, and I knew it had finally returned: a parade of fluffy white soldiers, dancing down from the sky and wrapping the barren trees and hills in a brilliant fleece. Snow!

As soon as I got the chance, I headed into the forest, dragging my legs through the snow, which was so heavy it seemed to intensify gravity. I felt like the first astronaut on a new planet, bundled up in layers and making the first impressions on the untouched duvet spread out in front of me. I kept pausing to savour it all: the taste of individual snowflakes on my tongue, their satisfying crunch under my feet. How fabulous the trees looked, clad in white and adorned with icicle pearls as if solemnly attending a winter ball. The way the snow muffled every movement into silence. And for one frozen moment in time, it seemed as if our planet had returned to normal.

When my family moved some 20 years ago from rainy London to the German countryside, I was thrilled to live in a place with what I considered a "proper winter". In January or February, the snow would usually stay with us for a few weeks – sometimes knee-deep and liberating me from school. I'd go sledging, build igloo-like caves, or my parents throwing snowballs for our dogs and – perhaps unfairly – laugh at their hopeless quests to retrieve them from mounds of snow. But over time, those spectacular winters turned into a mundane drizzle. In recent years, my parents – with whom I usually spend the winter – have rarely seen an inch of snow, and if they did, it quickly turned into slush.

I'm privileged to be distant from the most dramatic effects of climate change, like forest infernos or devastating hurricanes. Yet the silent transformation of winter's character can also weigh on one's psyche. To me, it's more than just a reminder of the wrenching planetary change we've caused and the hopelessness and anger I associate with it. There is something unique to witnessing the deterioration of this season. Some Nordic countries have words that come close to this feeling, like the Finnish "lumiahdistus", describing an anxiety related to desiring snow or not knowing whether it will come. In English, we might sum it up as "winter grief".

Driving this feeling, of course, is our species' burning of planet-warming fossil fuels and its influence on the sensitive process of snow formation. Snow falls as powder in air around -15C (5F) or slightly cooler. Slightly warmer, air holds more moisture, making snow denser, which could be why some areas are now seeing heavier snowfalls in the winter. Step over the critical threshold of 0C (32F) and you'll get rain. "There are a lot of regions that are very close to this threshold temperature, and that's why you see all these strong changes," climate hydrologist Ryan Teuling of Wageningen University in the Netherlands tells me.

BBC/Javier Hirschfeld/Getty Images

BBC/Javier Hirschfeld/Getty ImagesIn a 2018 analysis of Europe-wide weather station data, Teuling and his colleagues found that on average, the snow depth across the continent has declined by 12% a decade since 1951. While high altitudes in the Alps are still somewhat shielded from these effects, changes are pronounced at lower elevations, adds Gudrun Mühlbacher, who heads the regional climate office of the German Weather Service in Munich. In some German regions less than 800m (2,600ft) above sea level, the number of days with total snow cover has decreased by as much as half since 1970, Mühlbacher points out.

At just a few hundred metres above sea level, it's no surprise that at my family's home in the country's south-west, snow is becoming increasingly rare. That said, "snow has a very high variability from year to year", Mühlbacher adds. So even in a warming climate, extreme winters – like this year – can occasionally still occur without changing this long-term climatic trend. And, Teuling adds, if snow does fall, there’s a larger potential for the particularly heavy and destructive kind that crushes trees and roofs, and damages infrastructure.