Creativity: The weird and wonderful art of animals

A few animals are prodigious producers of ‘art’, says Jason G Goldman. Why do they do it? Do they enjoy the creative process? And is their work any good?

At first glance, the Vogelkop Gardener bowerbird is pretty boring. Its drab olive-brown plumage makes it hard to spot against the dirt on which it lives. However, a closer look reveals that this otherwise dull bird has a secret: the males build some of the most elaborate, aesthetically-pleasing objects of any bird.

Bowers are decorated structures that the males build to woo females. In some places they're tall towers made of sticks resting upon a round mat of dead black moss, decorated with snail shells, acorns, and stones. In other places, they're woven towers built upon a platform of green moss, adorned with fruits, flowers, and severed butterfly wings. Individual Vogelkop bowerbirds have their own tastes, preferring certain colours to others. The males place each item in their bowers with great precision; if the objects are moved, the birds return them to the original arrangement.

"Decorating decisions are not automatic but involved trials and 'changes of mind,'" wrote UCLA physiologist Jared Diamond, one of the first researchers to intensively study the birds' complex bowers. Diamond discovered that bower building was not innate, at least not entirely. The younger birds had to learn how to build the best bowers, either through trial and error, or by watching more experienced birds, or both.

Diamond concluded that bower building was a culturally transmitted creative process where each bird had his or her own individual tastes and preferences, and where each decision was made with intention and care. Bowerbirds, in other words, are animal artists – at least in sense that they take care in producing unique works that humans and birds alike find aesthetically pleasing.

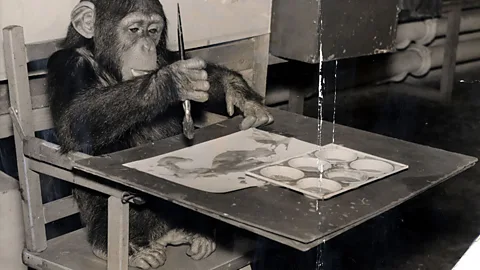

Bowerbirds aren't the only non-human artists. Congo was a male chimpanzee born in 1954 at London Zoo. When Congo was two years old, the British zoologist and artist Desmond Morris gave the chimp a pencil. "He took it and I placed a piece of card in front of him," Morris told The Telegraph in 2005. "Something strange was coming out of the end of the pencil. It was Congo's first line. It wandered a short way and then stopped. Would it happen again? Yes, it did, and again and again." Congo eventually graduated from pencils to paintbrushes. He and his art were featured on the British television programme Zoo Time, and in 1957 the Institute of Contemporary Arts featured his work in an exhibition.

While he never painted identifiable images – no portraits, no landscapes, no still lifes – Congo's style was unironically described by some as "lyrical abstract impressionism". He seemed to have a sense of intention in his paintings, and a sense of coherence. If his paintings or brushes were taken away before he felt he was done, he whined until they were returned to him. If he had completed his work, he refused to continue painting even at Morris's prompting.

In 2005, a set of three paintings by Congo, who created more than 400 works in his lifetime, were sold at auction for £14,400. In the same auction, an Andy Warhol painting and a Renoir sculpture went unsold.

Congo may have once been a zoological curiosity, a rare primate who was given the unique opportunity to express his artistic desires – or at least to smear graphite and paint onto a flat surface. But in the decades since he produced his first drawing, zoos have been giving paintbrushes to animals as a common practice. The hope is that these attempts at creative expression help keep animals happy.

While putting paintbrush to canvas isn't by any means a natural activity for a chimpanzee, elephant, or any other non-human animal, it is thought to help introduce some novelty into the lives of those animals. Painting is an activity through which the animals can exercise their minds, instead of just their bodies – “enriching” the otherwise boring captive environment. The idea is to stop the animals reverting to repetitive, compulsive behaviours. But does it work?

The jury is still out, and the benefits of creating art as mental exercise probably varies quite a bit from individual to individual. But at least one scientific study has been conducted on painting in zoo elephants, and the results are disappointing for animal art advocates.

The researchers focused on four Asian elephants at the Melbourne Zoo. They found that painting didn't reduce stress-related behaviours in the elephants, nor did it decrease repetitive or abnormal behaviours either before or after their painting sessions.

What that means, according to the researchers, is that painting "does not improve the welfare of elephants”. Given that, they suggest "its main benefit is the aesthetic appeal of these paintings to the public and their subsequent sale of which a percentage of funds might be donated toward conservation of the species". But since the study was limited to just four individuals, it is hard to derive wider conclusions.

Watch animal artists in action (UCL Grant Museum of Zoology/Rob Eagle)

Whether drawing or painting serves any useful purpose at the zoo, it is at least clear that humans are not the only animals capable of creating works of art, nor are we the only ones who appear to derive satisfaction from it.

Still, the simple act of transferring pigment to canvas isn't by itself necessarily an expression of creativity for animals, any more than it is for our species. The question of what constitutes art, of what qualifies as creativity, is something that human culture has grappled with for generations. After all, on appearances alone, some might lump Jackson Pollock's work together with Congo's; that could either reflect tremendous respect for the work of the chimpanzee, or contempt for abstract expressionism. Or maybe some will never appreciate animal art. One study in 2011 found that people were surprisingly good at spotting the difference between professional art and works done by chimps and elephants, and they preferred the human paintings.

So is animal art any good? That depends on your individual perspective.