The chefs reviving the Arctic's forgotten food

Aningaaq R. Carlsen/Visit Greenland

Aningaaq R. Carlsen/Visit GreenlandA group of revolutionary chefs in the Arctic and subarctic have ed forces to celebrate indigenous culture by developing a new kind of cuisine using traditional ingredients.

It is appropriate that I am on a boat in South Greenland when I try my first mouthful of fermented seal blubber, a buttery slice tasting not unpleasantly of the sea with a lingering note of fish oil, followed by a jaw-bustingly lengthy chew of the country's famous delicacy mattak, a square of scored whale skin, cartilage and fat.

That's because here in the Arctic, there is only a short distance between tundra and table, or as it is today, the sea and the serving dish: only a window separates me from the clear water, studded with icebergs, where the food was caught. Inunnguaq Hegelund, the award-winning indigenous Greenlandic chef introducing me to these dishes, is known in Greenland for his outstanding work with traditional meats, including polar bear, who are roaming on the rocky shoreline some hundred metres away.

Hegelund is part of a wider revolution happening in the Arctic and subarctic region, where he and a group of leading chefs and food entrepreneurs are reclaiming the indigenous food cultures of the past and developing them to create sustainable local food traditions for the future.

"I strongly believe that you have to know how to treat the food in your own backyard," Hegelund said, "When I was at culinary school, we took our bible from the French kitchen. We used the traditional French techniques with traditional French meats. When I started as a trainee, we never served local Greenlandic food – we even served fish from Spain! Now things are different."

The New Arctic Kitchen movement brings together the communities at the top of the world – including Arctic Canada, The Faroe Islands, Greenland and the Åland Islands in Finland – to share and develop their food cultures together. They have plenty in common: a sense of isolation, populations scattered in small coastal settlements and strong hunting traditions, setting them apart from the food cultures of the West.

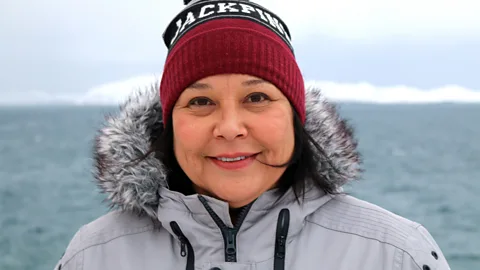

Rasmus Holm

Rasmus Holm"We're all ocean people," said Sheila Flaherty, a chef working in Nunavut, Arctic Canada. "We hunt and harvest in the same spirit, we butcher in an intimate way, and we eat in an intimate way. We live as Arctic people, and our Inuit homeland spans across the region."

Eating seal, whale, muskox and fish makes sense in locations where you're more likely to see a narwhal than a pig, cow or chicken. Eating local and sustainable food means eating these meats nose-to-tail, just like their ancestors have. Hunting of polar bear, seal and whale as a rule is strictly controlled by quota systems. In the Åland Islands, population growth of seals far outstrips the quotas given for hunters, who have historically never hunted the full 450 seals they are allowed per year; in Arctic Canada, there are no quotas for seal hunters because they are so plentiful.

The movement seeks to change the narrative around these traditional local food sources, to talk about them and inspire further development.

"The key idea is about exchanging ideas, taking best practices from each other and applying them to each community," explained Viktor Eriksson, former head chef at Restaurant Silverskär in the Åland Islands, Finland. "There is a lot of public funding for rural areas, but it is inefficient to do it individually. The best way to use it is to build on each other's ideas."

Rasmus Holm

Rasmus HolmFlaherty shares his ethos, citing a desire to work together as critical for the development of their food cultures, as well as a way to improve health in local communities, create local jobs and get a stronger sense of their culture. She has dedicated her working life to making it possible to eat indigenous Inuit food where she lives – which includes the likes of thin-sliced caribou liver, fermented seal fat and seal skin, and whales – and currently runs the guesthouse and restaurant Sijjakkut in Iqaluit, Canada.

"I want to share Inuit culture with the world," she said. "Ringed seal is my number one favourite dish to serve. I like serving it not to be controversial, but because the more we highlight and promote the seal, the less stigma we will have around it. It s our Inuit way of life."

Other indigenous delicacies from the subarctic and Arctic region include skerpikjøt, a Faroese dish of air-dried lamb that gains a funky, fermented taste akin to blue cheese as it dries, and Greenland lamb, grazed wild on scrubby, rocky grassland scented with thyme.

Aningaaq R. Carlsen/Visit Greenland

Aningaaq R. Carlsen/Visit GreenlandOne reason why the traditional diet has fallen out of favour is political: Danish colonists brought their food tastes to the Faroe Islands and Greenland; Nunavut was claimed by the British and subsequently Canada before gaining its own government. More recently, the desire to eat something different every night of the week has made "international" food look more attractive.

"Local people want to have variety in their diets," said Hegelund, "and they don't want to eat the same thing every day. So, it's about creating something different with the same meat."

The group is approaching this challenge by looking at the butchery and cuts of meat in particular, starting with seal. That means that instead of considering all the meat on the seal in the same way, diced, cubed and sold by the weight, they have identified that the loin and the shank taste better as a steak, and other cuts work well as terrine, sausage or jerky.

Variety is also coming from an unexpected source: greenhouses. The traditional cuisine of the far north is fish- and meat-heavy: it's a fact of life in a part of the world where vegetables and fruit can't be cultivated easily and are flown in and sold at eye-watering prices. But experimental greenhouses in south Greenland and Iqaluit are seeing positive results growing vegetables, leading to hope that imports can be reduced in the future.

Rasmus Holm

Rasmus HolmThe warming climate is also helping to make that possible, and climate change is very much on the radar of this movement. Being part of a hunting culture puts these communities on the front line, seeing environmental change as it happens, spotting new species and noticing changes in migratory patterns. Eriksson views running a sustainable food movement as a form of environmental stewardship: it depends on the local land being looked after.

"If you have people in the environment who care, they will help to take care of the recovery," he said. "If they are not allowed to hunt, fish and sustain themselves from nature, they will lose interest. That's the most dangerous thing that can happen.

"We know things now that we didn't know 100 years ago. In days gone by, seals and whales were exploited from the Arctic and extracted to the rest of the world. But if the Arctic takes a sustainable proportion to feed itself, it won't be depleted. Sending it to the rest of the world – that would be a problem. We can't do it like that anymore."

There's a sense of urgency in working with this food before it's too late.

Rasmus Holm

Rasmus Holm"We need to record our traditional food and the traditions behind them," said Hegelund. "It isn't well-documented and it needs to be done now, before the generations behind it die."

For the future, goals include both strengthening food tourism for the region and introducing New Arctic Food into institutional settings, such as elder care centres, hospitals, kindergartens and schools.

In Greenland in particular, talk of independence from Denmark is never far away. Increased trade routes and the money that could flow from the region's international mining interests potentially herald an era where it can garner more power and reclaim its indigenous culture. Hegelund sees it as a marker of independence for his country as it emerges from its colonial past.

"The biggest thing for me is that we can stand on our own with our own food," he said. "It's so important: if you want to be an independent country, you need your own food."

---

Seal loin with pickled unripe apples, potato purée and juniper

By Viktor Eriksson

(serves 4)

Ingredients

500g seal loin

500g peeled potatoes

2dl cream

50g butter

100g pickled unripe apples

10 fresh juniper berries, preferably green

salt

Method

Step 1

Trim the seal loin meat and season with salt.

Step 2

Sear it in a very hot dry pan or directly on the stovetop and let it rest in a 150°C oven until 52°C in the centre.

Step 3

Cook the potatoes in the cream and butter, add a little water if it's not covering them. Mix into a smooth purée when cooked.

Step 4

Using a mandolin, slice the pickled unripe apples very thinly.

Step 5

Slice the seal and garnish the slices with apple pieces and chopped juniper berries.

Step 6

Serve with the potato purée and vinaigrette as a sauce.

BBC.com's World's Table "smashes the kitchen ceiling" by changing the way the world thinks about food, through the past, present and future.

---

more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.