What Japan’s love of nostalgia says about its economy

Yuko Komura

Yuko KomuraDespite being thought of as being at forefront of cutting-edge technology, Japan maintains a quiet relationship with all things analogue

Nippori, Tokyo is known for its “old-town” vibe, bustling with shoppers in its wholesale district and street arcades. It is here, amongst retro retailers, that a camera shop opened for business in 2016. Displayed in a glass case that spans the entire wall of the shop, are cameras that radiate with nostalgia.

A customer walks into the store asking for new batteries. He pulls out from his bag, a Swedish film camera manufactured about 40 years ago. For roughly 15 years, the man has used digital cameras, but ing he had this camera stashed away in his childhood home, he decided to bring it out for use.

Mitsuba-dou Camera Shop specialises in repairs and re-sales. The newest digital camera is not available here; the store only deals in old-fashioned film cameras. Shinichiro Inada is the young owner who turns 31 this year. Skilfully, he exchanges the battery and inserts new film into the camera. “Now you can use your camera again,” Inada said, returning the camera to its owner. The customer is pleased; he will be going on a photography workshop next weekend.

Yuko Komura

Yuko Komura“Our customers include photographers who have used film cameras for 50 years, and novice s who have never touched a film camera before,” Inada says, “The majority of our customers are 10 to 20-year-olds. It seems they ire the unique look of film camera pictures posted on social networking sites such as Instagram.”

Hi-tech or lo-fi?

Japan is generally thought of as “hi-tech”. The Sony Walkman, Nintendo video game consoles, mobile phones, and QR codes are a few examples of Japanese technology that swept the world.

According to the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), Japan’s budget in research and development for industrial technology ranks third after the United States and China. Japan excels globally in areas of household electronics, robotics, automobiles and space development.

At the same time, Japan has an analogue culture; as if to shun cutting-edge technology, there has been a preferential rise in analogue, such as film cameras.

An analogue-lovers playground

“For anyone that loves analogue, Japan is like heaven,” says Bellamy Hunt, a film camera enthusiast from England living in Tokyo’s Kichijoji neighbourhood.

After travelling the world, Hunt chose Japan as his base in 2004 and seven years later started his online film-camera store “Japan Camera Hunter.”

Yuko Komura

Yuko KomuraPrior to that, Hunt had spent two years working at an established camera shop trusted by professional photographers. He learned from experience that, in Japan, no mistakes are tolerated – everything has to be “100%.” In addition to selling and servicing cameras, Hunt learned to develop film and handle products in the correct way, and aimed to provide the best service to his clients. He realised that, in turn, his customers cared for their cameras and that maintaining the tools of their professional craft is a form of expression and pride in their work.

More from Japan 2020:

A dramatic fire-seared delicacy

Hunt believes it is this attitude of care that separates the quality of film cameras available in Japan. Most film camera enthusiasts today buy their cameras through the secondary market. Compared to film cameras available abroad, the cameras sold in Japan have less dust accumulation, fewer missing pieces, and are mostly in mint condition.

Japan Camera Hunter

Japan Camera HunterHunt says that “accessibility” is another distinction of Japanese film camera culture. For the past several decades, film cameras have garnered not just a handful of fanatical fans but are also popular within a larger base. Both “cheki” (the nickname for an instant Polaroid-style camera from Fujifilm) and “utsurundesu” (a disposable, single-use camera, also from Fujifilm) are affordable and have been long-time best sellers since their market debut over 20 years ago. In major cities there are electronic megastores, and second-hand shops that deal in film cameras, giving people access to cameras from all over the world.

Hunt offers poignant advice: when buying a film camera, be respectful. Having good manners is an important rule for the Japanese. Smile at the sales clerk when you walk into the store. Handle the merchandise with care. They will then be only too glad to show the best in stock.

Visual art

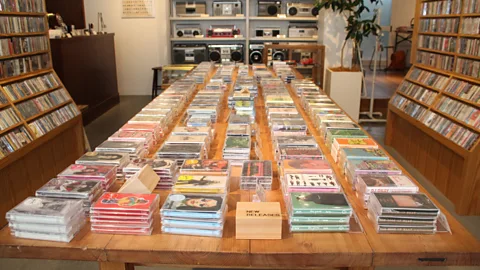

Within the streets of Tokyo’s Nakameguro neighbourhood is Waltz, a rare shop in today’s world that specialises in selling cassette tapes. Opened in 2015, the store boasts a collection of over 6,000. Against the unique wooden interior, the bright jackets of the cassettes don’t look at all retro or nostalgic.

“Cassette tapes are not old items of the past, but part of a new and expanding music culture,” explains Taro Tsunoda, the owner of Waltz. Although the shop also sells older second-hand cassettes, their main focus is actually new tapes.

Yuko Komura

Yuko KomuraAccording to Tsunoda, since 2010, there has been a surge in artists, mainly from the west coast of America, who have re-released tracks in cassette form. As a result of this, cassette tapes have been re-evaluated on a global scale. Music analytics company BuzzAngle Music reported that cassette tape sales has seen a dramatic rise in 2018, up 18.9% from the previous year alone.

“The rectangular packaging on the cassette tapes are like art books created by the musician. My shop, therefore, is here to present their work as visual art,” says Tsunoda.

He designed the shop’s interior in the image of a modern art gallery. For new releases, Tsunoda hand-writes how and why the album should be enjoyed on cards. Even the second-hand cassette tapes are in wrapping, and in pristine condition. There isn’t a single cassette out of place. “The attention is in the details. Perhaps that is very Japanese of me,” says Tsunoda with a laugh.

Yuko Komura

Yuko KomuraOver half of the customers that visit Waltz are foreigners, and while many work in the music industry, there are professionals in fashion and design as well. In 2017, Waltz was listed as a “Gucci Place,” highlighting it as somewhere that inspires the luxury brand.

“As an item, cassette tapes are undeniably attractive. With digitalisation and streaming, music has morphed into ‘nothingness’. But I believe music should be a tangible item. Something you can physically touch, see its cover, and then feel its vibe. Outside a shop, you can’t get that experience,” Tsunoda says.

Status quo or future-leaning?

Akira Takamasu, vice president of Kansai University and professor of sociology, says “Japan’s analogue culture is directly correlated to the country’s economic growth.”

Takamatsu started the university’s first venture project in 2001, heading up an indie record company, and creating music alongside students.

“Records have a unique warmth and depth to [their] sound, which is why there are people who still love vinyl. But that isn’t the only reason people prefer records,” he says. “The audio boom occurred in Japan during the ‘70s, which coincided with the post-war economic bubble. People started to feel monetary security which allowed spending, not just of everyday necessities, but in new cultural phenomena – which, at that time, was records.

Takamasu explains that putting on a record became analogous with being at the forefront. “Knowledge in records was regarded as high-status,” he says.

He points to the last quarter-century’s economic stagnation in Japan as what’s driving a love for retro. “If social mobility hasn’t improved for 25 years – which is more than half of a worker’s career – then buying into trends becomes more expensive,” he says. “Perhaps going back to old retro habits reflects a Japanese attitude that embraces the other side of stagnation.”

Whatever the reason – a sluggish economy, hipster spending habits, or simple nostalgia – Japan’s love of old gadgets proves that if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.