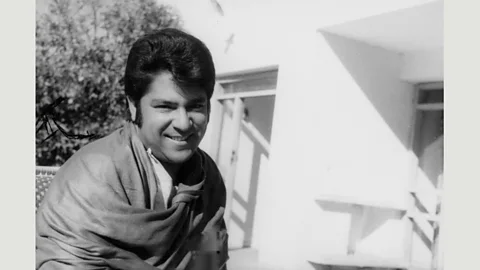

Ahmad Zahir: The enduring appeal of the Afghan Elvis

Shabnam Zahir

Shabnam ZahirA new documentary celebrates Ahmad Zahir, the ‘60s and ‘70s icon who mysteriously died in 1979. Arwa Haider talks to the people making the film, including Zahir’s daughter, about how the singer combined popularity with protest.

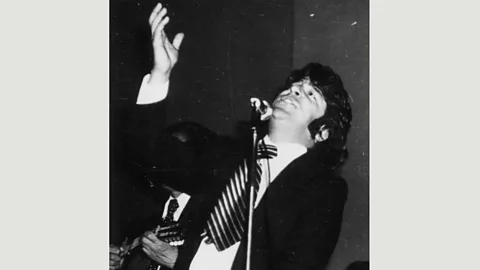

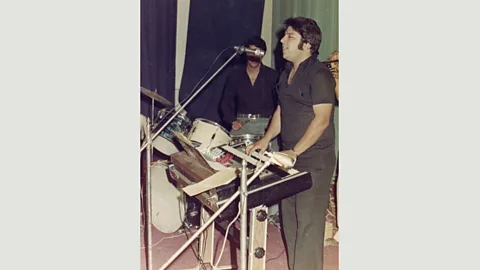

There is some dream-like footage online of a 1970s gig at Kabul’s Intercontinental Hotel, showing an energetic figure leading a multi-instrumental band. The performer’s hip looks (dark quiff and sideburns; loosened tie) and rollicking, psych-roots grooves reflect the ‘Afghan Elvis’ nickname he earned.

Shabnam Zahir

Shabnam ZahirThis was Ahmad Zahir, pop culture sensation and the son of Afghanistan’s former prime minister: during a booming ‘golden age’ in the ‘60s and ‘70s, he was a prolific recording artist and a music idol for the masses. Zahir’s music drew from Persian poetry as well as Indian classical styles, and it increasingly revealed a political edge, criticising the Soviet-backed Marxist regime who had seized power in Afghanistan following a 1978 military coup.

More like this:

- Amazing images from Iran’s swinging ‘70s

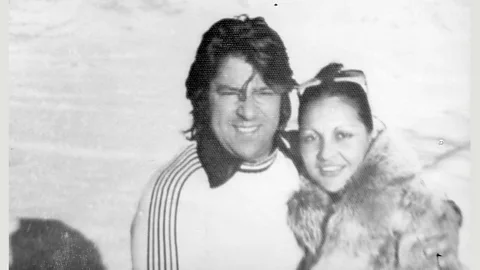

On 14 June, 1979, his 33rd birthday, Zahir died in mysterious circumstances (officially a car crash, but some have questioned that). On hearing the news, his pregnant wife Fahira went into premature labour, giving birth to a baby girl, Shabnam. Nearly 40 years later, Shabnam and US film director Sam French are collaborating on a Kickstarter-funded documentary about her father’s life.

Shabnam Zahir

Shabnam Zahir“If there’s a common thread that brings Afghans together, it’s my father’s music,” Shabnam Zahir tells me, from her home in the US. “There are so many ethnic groups in Afghanistan; he tuned into that, and would do concerts in all these different locations. He’d change people’s views of one another.”

Despite never having the chance to know her father personally, Shabnam Zahir has grown up with a sense of his legacy. Her half-brother Rishad (from Zahir’s first marriage) has also pursued music and Dari literature. Shabnam is conscious that for all the Western prime-time political coverage about Afghanistan, the country’s musical and cultural heritage is largely overlooked.

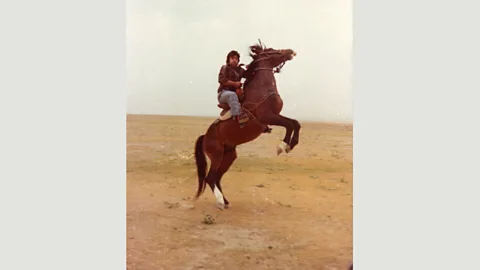

“The media exposure that is so clouded with negativity and despair… it’s heart-breaking,” she says. “As young Afghans who grew up in Europe and the States, that’s not what we were told. Women would dance the shimmy and the twist at my father’s concerts, and they’d have no reservations about it! Now, his music takes listeners back to a country that was progressive and hopeful.”

Shabnam Zahir

Shabnam ZahirShe has her personal favourite tracks from her father’s catalogue; she picks out the swirling, spiritual melody of Ay Qawme Be Haj Rafta (based on Rumi’s poem, O You Who Have Gone On Pilgrimage), and by contrast, the polemical Zindagi Akhir Sarayat, which the government banned from radio airplay. She explains: “Translated to English, the song’s refrain is: ‘Freedom and liberty mean life to mankind. There’s no need for submission, fight for your freedom.’”

Film director French first encountered Ahmad Zahir’s music when he visited Afghanistan in 2008; French’s intended brief trip actually became a stay of several years, as he was inspired to create films including the Oscar-nominated short Buzkashi Boys (2012).

“He [Ahmad Zahir] provided a window into the complex cultural landscape of an often misunderstood country, a place with a rich tradition of music and art,” enthuses French. “I became ionate about making films that showed another side of Afghanistan than the one we see on the news, and the story of this remarkable man presents the perfect opportunity to explore a country that most people in the West have never seen.

Shabnam Zahir

Shabnam Zahir“My hope is that in these times of strife, with tribalism and xenophobia on the rise, the story of Ahmad Zahir can show how art and music can unite us.”

Marching to a different beat

The British musician and academic John Baily has devoted decades to the research of Afghan music, originally moving to the city of Herat with his wife, fellow ethnomusicologist Veronica Doubleday, in the mid-‘60s. In his richly layered book War, Exile and the Music of Afghanistan, Baily explores Afghanistan’s music culture from 1970 onwards (noting that the “wealthy and cosmopolitan” Ahmad Zahir “when not accompanying himself on the ‘armonia or piano accordian… was accompanied by instruments such as trumpet, electric guitar, and trap drum set, instruments not available to the average amateur enthusiast”).

Shabnam Zahir

Shabnam ZahirBaily charts the rise of the US-backed mujahideen, the era of Taliban rule, and a sense of modern recovery with the Afghanistan National Institute of Music, founded by musicologist Ahmad Sarmast in 2010. Baily also notes that in 2011, a Kabul FM radio station was dedicated solely to the songs of Ahmad Zahir.

“Ahmad Zahir is a legend for Afghanistan, for all generations,” declares the genial Sarmast, when I call him in Kabul. “It was about the style of his performance, and his musical forms; there are a lot of adaptations from Indian music, Western forms adapted with beautiful poetry, a strong folk music influence, and a sense of social responsibility… the variety means everyone can find themselves in Ahmad Zahir.”

As a student, Sarmast attended several of Zahir’s concerts: “He was extremely lively on stage, full of movement and happiness – that distinguished him from other singers in Afghanistan,” he recalls. “Every single concert was sold out; the audience would be on the dancefloor in front of the stage, clapping to the rhythm of each particular song.”

Shabnam Zahir

Shabnam ZahirHe also clearly re Zahir’s death: “In reality, it was a day of national mourning,” he says. “Afghanistan was slowly becoming a police state, yet there were hundreds of people carrying Ahmad Zahir’s body to state – and I was one of those people. We left our school to the crowds.”

Soft power

Sarmast left Afghanistan during its ongoing civil war in the ‘90s, and continued his musical studies in Russia and Australia. He returned to launch the Afghanistan National Institute of Music; his own father, the eminent Afghan musician, composer and conductor Ustad Salim Sarmast, had been an orphan, and Sarmast was inspired to create life-changing opportunities for disadvantaged students. He has faced extremely serious risks in the process: in 2014, he was nearly killed in a Taliban bomb attack – surgeons removed 11 pieces of shrapnel from his head, and restored partial hearing after both his eardrums were torn.

His resolve and ion seem to have been reinforced, as the Institute has flourished, spanning varied Afghan and Western classical disciplines; it currently has around 250 students, a third of which are female – in 2019, he will also take its all-female Zohra Orchestra on a European tour.

“Everyone has an opportunity here, including the poorest of the poor and middle-class kids,” says Sarmast, warmly. “We are practically a beautiful mosaic of the ethnicities of Afghanistan.” He explains that the Institute’s ensembles represent a continued link with the ‘golden age’ of Radio Afghanistan, when the airwaves were a hotbed of orchestral talent and music innovators including Ahmad Zahir. And he expresses a fervent, fearless belief in the enduring ‘soft power’ of music.

“Music is not just entertainment; it is vital for healing – and it is what this country needs more than anything, after 40 years of war,” says Sarmast. “You can beat the Taliban in the battlefield, but to win in the long term, you need to present an alternative to the community. Investment in arts, culture and education is as important as investment in security. Music is also a basic human right.”

By bringing Zahir's legacy to broader audiences, that soft power is channeled for new generations of Afghan talent.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.