Was Threads the scariest TV show ever made?

Alamy

AlamyThis week marks the 35th anniversary of the TV premiere of the British nuclear war drama – which was dubbed “the night the country didn’t sleep”. It remains brutal – but essential – viewing, writes Ross Davies.

In the garage of Mick Jackson’s Los Angeles home there is a portrait. The British director recognises himself in the painting, as a younger man – but there is something not quite right.

“I look at the eyes and they terrify me,” Jackson, now 75, tells BBC Culture. “They’re completely haunted.”

Jackson sat for the portrait shortly after he’d finished making Threads, the nuclear war film. It premiered on the BBC on 23 September, 1984, which was described as “the night the country didn’t sleep”. According to Jackson, so immersive was his experience behind the camera that “it took years to get out of my head”.

More like this:

Threads was born out of an era of paranoia – the early 1980s. In 1983, US President Ronald Reagan had launched the Strategic Defense Initiative – also known as ‘Star Wars’ – a program designed to develop an anti-ballistic missile system to fend off a nuclear attack. In the same year, Reagan referred to the Soviet Union as an “evil empire”.

As tensions escalated between the US and the USSR, so speculation fomented that nuclear war was not so much a far-off nightmare, as an imminent possibility. Historians now compare those days of 1983 to the Cuban Missile Crisis two decades earlier as one of the most perilous episodes of the Cold War.

Overcome by a sense of urgency, Jackson – then a documentary maker at the BBC – first set about producing an episode for science series QED, entitled A Guide to Armageddon. Jackson describes it as an “unbiased, factual, emotionless piece of television” that asked the simple question: what would happen to us in the event of a nuclear fallout?

While viewers who caught A Guide to Armageddon may have well felt a sense of unease, it would little prepare them for Jackson’s next project, given the green light in late 1983.

Kitchen sink realism

The opening scene of Threads is as unremarkable as it is familiar. We meet young lovers Ruth and Jimmy, canoodling in a car on the edge of the Peak District, UK. Chuck Berry plays on the radio, while they overlook their home city of Sheffield, whose state of repose – smoke gently wafts from a cooling tower – is all but a distant memory by the time the credits roll two hours later.

We soon learn that Ruth is pregnant, much to the consternation of both sets of parents, who hail from differing sides of the British class divide (Jimmy is working class, while Ruth is middle class). Yet the two are resolute they’ll make a go of it and prepare to get married and settle down to start a family.

These opening exchanges are indebted to the British kitchen sink realism of the 1960s, best popularised on film by the director Ken Loach. Indeed, Threads was written by Barry Hines, who adapted one of his own novels into the script for Loach’s 1969 masterpiece Kes. Hines was a proud Yorkshireman, and the dialogue in these first scenes – at the dinner table, the pub, the timber mill – carries all of his trademark ear for the demotic.

“Barry really knew how to write characters and human relationships,” Karen Meagher, who played Ruth, tells BBC Culture. “What you’re seeing in those first few scenes are ordinary people – real life. Everyone knows a Ruth or Jimmy.”

Yet, while the people of Sheffield go about their everyday lives, television and wireless bulletins in the background carry news of growing tensions between the US and Soviet Union in Iran. At first, they are given short shrift, before it emerges that the situation is more serious than it first appeared. Soon, news reports of an imminent attack on the UK are front and centre. In the grip of panic, a siren wails and a four-minute warning is issued.

And then it happens.

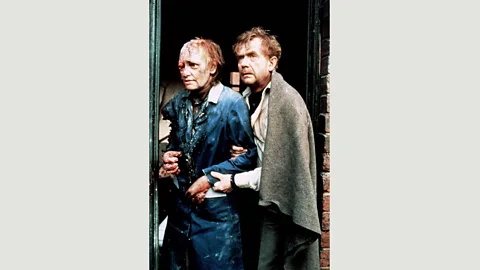

It’s hard to conceive of a more brutal five minutes committed to film than what takes place around the 46-minute mark of Threads. In sheer terror, a woman urinates down her leg. It’s only the beginning. Amid the thermonuclear blast that follows, windows smash; walls disintegrate; buildings crumble; human life melts as a firestorm engulfs Sheffield. The soundtrack to destruction is a rumble so distressing that it is comparable to an “enormous door slamming in the depths of hell”, as the noise of a nuclear explosion was described in Peter Watkins’ similarly terrifying 1960s film The War Game.

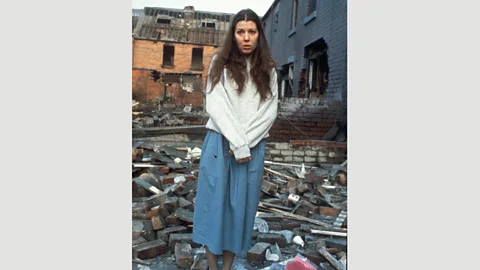

But it is Threads’ depiction of the subsequent nuclear winter that lingers long in the mind. Amid the scorched ruins, we follow Ruth’s struggle for survival (her parents die soon after the blast while Jimmy is never seen again) in a post-apocalyptic world ridden by famine and disease. In the scramble for food – now civilisation’s only currency – law and order collapses, eclipsed by anarchy and authoritarian rule.

This is a world in which the living envy the dead. In which hospitals, divested of the means to exercise proper care, carry out amputations on patients without anaesthetic. In which Ruth – having given birth to a daughter – is forced to trade her body for rats as a form of sustenance. Where children of the survivors of the apocalypse roam the land, mute due to there being no education system of which to speak.

“There were a couple of times during filming, where I thought: ‘should I be making this?’” its Jackson, who shot Threads over 17 days on a budget of just £250,000.

“But I just tried to that this was my one chance of making a film like nothing people had ever seen before. We couldn’t hold back, because to do so would have been to not tell the truth. People had to see it.”

‘Too horrifying for TV’

Talking to Jackson – who went onto enjoy Hollywood success, directing the 1992 blockbuster The Bodyguard – what is immediately impressive is his knowledge of his subject matter. In researching the potential impact of a nuclear fallout, he spent months meeting with scientists, doctors and defence specialists.

Over the phone, he speaks with authority on everything from the history of arms control to the renewal of the New Start treaty – the only existing arms control pact between the US and Russia. “Sorry to be so wonkish about this dreadful stuff,” he apologises at one point.

But if Threads hadn’t had Jackson’s eye for realism, it would surely have been to its detriment. Even the shoestring budget, which limited the makeup for burns victims to a mix of tomato ketchup and Rice Krispies cereal, does nothing to detract from the horror that unfolds.

“I suppose when you watch it now, you can see we didn’t have a lot of money in certain scenes,” Meagher laughs. “But that’s not what’s important. It’s about human condition, love and loss – that’s what will always be important to people watching it, regardless.”

Threads isn’t the only film from the time to represent destruction at the hands of a nuclear attack, but no other comes remotely close to its unremitting bleakness. In 1983, ABC broadcast The Day After, a television film, which, like Threads, imagines how a fallout impact would impact on ordinary Americans, leading ordinary lives on, seemingly, just another ordinary day. Substitute Sheffield for Kansas City and you have the same premise.

Alamy

AlamyBut, with its $7 million budget, and star cast – led by Jason Robards – The Day After packs not even half the punch of Threads. It’s almost Disney-esque in comparison. If there is one nuclear war film to which Threads doffs its cap, it is the aforementioned The War Game (1965). A 46-minute docudrama produced for the BBC, the film was pulled due to being, as the broadcaster put it, “too horrifying for the medium of broadcasting”. A young Mick Jackson saw it at an independent screening on his college campus.

Few who have seen Threads forget its impact. Toni Perrine, professor of film at Grand Valley State University, Michigan, recalls watching it shortly after it debuted on television in the US in 1985 (prefaced, unusually, by a personal introduction by TBS founder Ted Turner).

“I was pregnant with my second child at the time and Threads shook me to the core,” says Perrine. “I was literally nauseated by the final scene of the film.”

At his home in a small village in Oxfordshire, a 13-year-old by the name of Charlie Brooker also watched Threads on the night of 23 September.

Netflix

NetflixSpeaking on BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs last year, Brooker cited the film as a formative moment of his early adolescence. “I watching Threads and not being able to process what it meant; not understanding how society kept going,” he said. “I assumed it [nuclear war] was going to happen.”

There are clear parallels between Threads and Brooker’s dystopian science fiction series Black Mirror. Both, in Brooker’s words, are “about the way we live now – and the way we might be living in 10 minutes' time if we're clumsy”. Mankind forever teeters on the brink – it’s only our perception of this that alters.

Towards the end of our interview, I ask Jackson to define Threads’ genre. Is it a drama? Docudrama? Sci-fi? Horror?

“I don’t believe it’s too bold to say this, but it is just Threads,” he says. “That’s its genre.”

Did you enjoy this story? Then we have a favour to ask. your fellow readers and vote for us in the Lovie Awards! We're nominated for Best Website - Television & Film and Best Overall Social Presence. It only takes a minute and helps original, in-depth journalism. Thank you!

Love TV? BBC Culture’s TV fans on Facebook, a community for television fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.