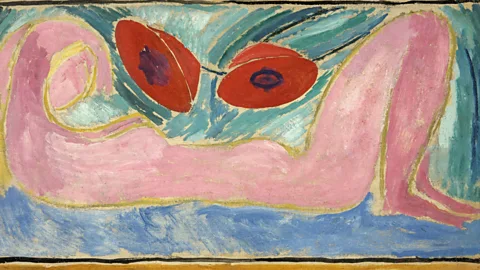

The art of the ménage à trois

Swindon Art Gallery

Swindon Art GalleryThe exhibition Modern Couples shows how artists and writers have been fluid in life, love, sex and creativity. Holly Williams explores some avant-garde threesomes.

Brangelina, Kimye, Hiddleswift… you could be forgiven for thinking the celebrity portmanteau name was an invention of the 21st Century. But today’s creative couples surely have nothing on the delightful ‘PaJaMa’: an amalgam of Paul Cas, Jared French and Margaret French, to reflect the interdependence of their relationship and artistic practice. From 1937 on, they lived as a polyamorous trio for 20 years.

Collection Jack Shear/ Gitterman Gallery New York

Collection Jack Shear/ Gitterman Gallery New YorkPaJaMa is one of the fascinating , lesser-known stories in Modern Couples, a new exhibition at the Barbican in London. A collaboration with Centre Pompidou-Metz in , the show refutes the notion of the solo – and let’s be honest, usually male – genius. Instead, it re-examines creative partnerships of the first half of the 20th Century to explore their symbiotic nature. Featuring more than 40 couples (narrowed down from a longlist of more than 200), it takes a wide-ranging look at how the artistic and literary experiments of the avant-garde were often also accompanied by experiments in living, and in loving.

But although it’s called Modern Couples, one of the striking things about the exhibition is just how fluid, porous, or expandable many of these relationships were. Actually, we’re often not talking about couples – but ‘throuples’. Two’s company, three’s an experiment…

“‘Couples’ is an elastic term,” the curator Jane Alison suggests. “And of course, three-way relationships are not easy, but there are a number within this exhibition.” Some form a cheerful – some a fraught – ménage à trois. Some come to quiet arrangements within existing marriages, while others espouse an open relationship as a radical, political act.

We seem to be in an era that’s freshly questioning of conventional relationship structures, and more open-minded towards alternatives. Or more nosey, at least: barely a day goes by without a new article about polyamory, ethical non-monogamy, or relationship anarchy. The language and terminology may be different, but many of the ideas are the same as those wrestled with – practically, romantically, creatively – by the 20th-Century avant-garde.

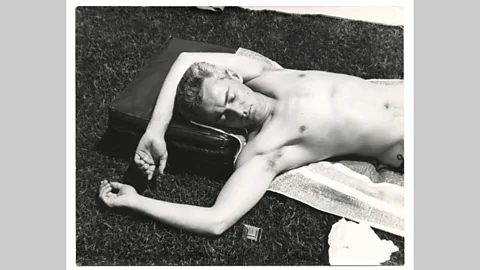

Collection Jack Shear

Collection Jack ShearBack to PaJaMa. The trio met in New York City, at the Art Students League. Paul Cus – who painted stylised, muscular, sometimes homoerotic scenes – and Jared French, also a figurative painter in what was dubbed the ‘magic realism’ style, became lovers. Jared married Margaret in 1937 – and so began a new, fluid, three-way relationship that also found expression in tly-made photographs.

Their work is associated with Fire Island, which runs south of Long Island, and which was already a gay enclave by the mid-1930s. The trio’s photographs are sometimes surreally playful, often moodily atmospheric, and always elegantly posed and poised. Long, lithe bodies drape on sand dunes or languish in the shallows; modesty is covered by driftwood, draped towels, or nothing at all.

1937, Estate of George Platt Lynes/ Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York

1937, Estate of George Platt Lynes/ Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New YorkThey shot each other, and their friends – but these carefully composed photographs were a private project, only shared among their circle, until discovered in the 1980s. “Art was the place where you could experiment,” Alison tells me at the show’s opening. “They were discreet, publicly, but were able to enjoy in their artwork this liberated space.”

All images are credited to all of them, simply as PaJaMa: an act of naming that’s obviously playful, but surely also boldly celebratory of their erotic and artistic union.

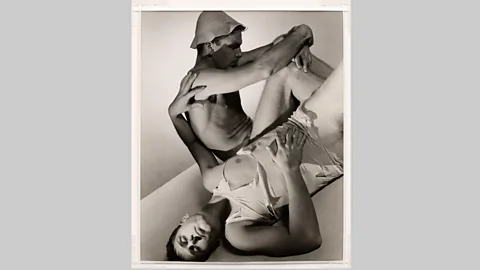

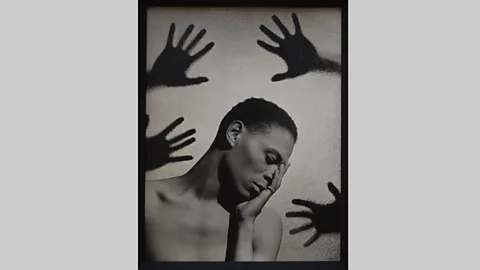

PaJaMa photographed, and crop up in photographs by, another threesome featured in Modern Couples: George Platt Lynes, Glenway Wescott and Monroe Wheeler. Lynes was behind the lens; as with PaJaMa, there’s cool elegance to his performatively homoerotic black-and-white photographs, but something of the candour of his portraits also feels strikingly modern and hip. It’s no surprise that he enjoys a cult following, and inspired Robert Mapplethorpe.

Wheeler – director of publications at MoMa – was already in a relationship with Wescott – a successful novelist – when Lynes arrived on the scene in the 1920s. Their ménage à trois was not without its tensions: Lynes rather replaced Wescott in Wheeler’s affections – or in his bed at least, Wescott often the one that had to sleep alone.

Estate of Geroge Platt Lynes/ Beth Rudin DeWoody

Estate of Geroge Platt Lynes/ Beth Rudin DeWoodyWescott was also attracted to Lynes, but it wasn’t reciprocated. An extensive extract from his diary in 1937, reprinted in the show’s catalogue, conveys his “gnawing desire” for his lover’s lover, going into really rather extensive detail about Lynes’ penis.

Was it healthy or weird of Wheeler to encourage Wescott to explore all this in his writing? Readers benefitted, at least: “Wescott wrote this amazing book, The Pilgrim Hawk, which deals with his sexual frustration – Monroe Wheeler encouraged him to make his own experiences the subject of his work,” Alison explains.

In 1943, after 17 years, Lynes left the relationship – but Westcott and Wheeler endured, spending a total of 68 non-monogamous years together.

Free love

Elsewhere, openness in relationships was a political act. In Russia, the revolution extended to marriage: the need for sexual freedom and the liberation of women was part of some Marxist theories. Among avant-garde artists, monogamous marriage was deemed rather bourgeois.

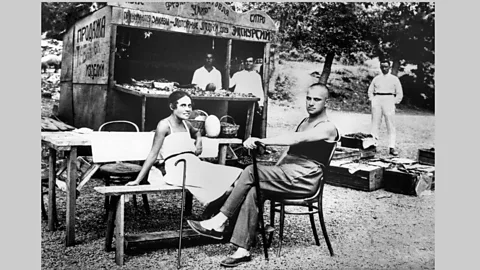

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSo when Osip and Lilya Brik saw Vladimir Mayakovsky reading a poem at a party in 1915 – and both “fell ionately in love with him”, according to Emma Lavigne, director of the Pompidou-Metz – it was no disaster. Indeed, when Osip found out Lilya had slept with Mayakovsky, he’s reported to have replied: "How could you refuse anything to that man">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });